|

Patagonia is more than a brand name on outdoor gear - it is an incredibly thrilling region at the southern end of South America where only Drake’s Passage around The Horn separates it from Antartica. It is the southern end of the longest mountain range in the world - the 5,530 mile-long Andes range which forms the western edge of South America running from Venezuela to Chile and Argentina.

The entire Southern Patagonia ice field from

the International Space Station (courtesy NASA)

The area is so big that I had to find a photo from NASA’s Earth Observatory taken from the International Space Station over Argentina’s Patagonian steppes in order to show it all in one shot. The three huge lakes at the base of the photo hold water melted from the glaciers that flow out of the Southern Patagonia Icefield or SPI, the largest ice mass in the southern hemisphere of Earth excepting Antarctica. It covers more than 6,000 square miles and is so big that the water from its melting ice at the western edge flow into the Pacific, while the eastern edge melts into the Atlantic.

There are 24 national parks in Chile’s portion of Patagonia and 11 more in Argentina in addition to three Argentine national monuments. Both Chile and Argentina use their park systems to preserve the untouched wilderness within their borders and to return vast areas that have been touched by human activities back to their wild states. In his Netflix documentary Our Great National Parks, former President Barak Obama commented that “This region is rapidly becoming one of the most protected places on Earth.” The documentary is well worth watching—beautiful photography and well-told stories of returning large tracts of land to their wilderness states.

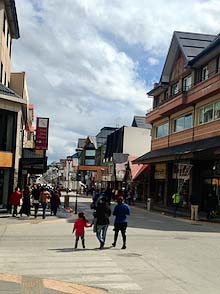

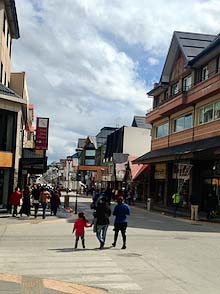

Scenes of the town of El Calafate, Argentina |

Our most recent visit began on the Argentinian side, in El Calafate—a town of 25,000 that exists principally on tourism because it is on the southern edge of the Lake Argentino, the country’s largest freshwater lake. The lake covers more than 500 square miles with an average depth of over 500 feet, all fed by glacial melt. It is the jewel in the crown of Los Glaciares National Park which has no fewer than 47 major glaciers. The Perito Moreno Glacier, the biggest glacier in the world that is accessible by land, has a front wall nearly 200 feet high. It can be reached by road or trail or by boat on Lago Argentino which is, itself, a show to be treasured.

Perito Moreno Glacier from the road, the trail and the boat |

We boarded a boat to get closeup looks at the glaciers and the icebergs that they release as well as tremendous views of the surrounding mountain peaks.

Taking the boat on Lago Argentino |

As we cruised, we passed huge icebergs that had calved off some of the glaciers.

Icebergs that had calved off Perito Moreno |

The mountains surrounding the lake were an impressive start to our peak-watching.

The mountains surrounding Lago Argentino

When we got to the wall of the Spegazzini Glacier—which towers over the lake surface even higher than Perito Moreno (nearly 440 feet)—we needed some method of demonstrating the sheer size of that enormous wall of ice. As luck would have it, another cruise ship sailed up to its base. Look very carefully at the left edge of the photo. That tiny object in front of the lower left of the glacier is really a big cruise ship!

A ship at the base of Spegazzini Glacier

But the edges of these glaciers, as monumental as they are, are just a fraction of the ice mass that constitutes the glacier. Behind the front of Perito Moreno are nearly twenty miles of ice covering almost a hundred square miles to a depth of over 500 feet. Portions of Spegazzini are even thicker than that.

The massive amounts of ice behind the faces of the glaciers |

After two days on and around Lago Argentino, we hopped on a bus that took us over some of the Patagonian Steppes with the towering Andes on the horizon. We passed from Argentina to Chile through a remote border crossing on Route 250.

Then we headed for Puerto Natales, population 18,000. It is a picturesque town of friendly people boasting large murals and interesting public art.

Public art in Puerto Natales, Chile |

The town is the jumping-off point for Chile’s Torres del Paine, a 700 square-mile national park that gathers a quarter-million visitors a year. The park includes Lago Grey at the foot of Grey Glacier. That is another huge glacier coming off of the Southern Patagonia icefield. We tried to sail to Grey Glacier, but rough weather forced our pilot to turn back. We had some inkling that might happen. In order to board the boat, we had to hike past a trickling stream, over a fast flowing river, through some woods and across a third of a mile of sandy gravel to find where the Grey III, a 98-seat catamaran, had been beached to take on passengers. When we did board, the first thing we noticed was that bright orange life vests were not stored under the seats, but out on the tables in front of the seats.

Our aborted effort to sail to the glaciers |

Once we got underway it didn’t look too bad until we cleared the lee of the peninsula on which the ship had been beached for us to get aboard. Most of our views were through rain splattered windows as the ship rocked and rolled out into the wind, and then finally turned back toward shelter. And yes, although it was a disappointment, we got our money back.

Lago Grey through rain-splattered windows |

Torres del Paine, as famous as it is for glaciers, is also an amazing place to view jagged mountain peaks. Indeed, the “Torres” in its name may mean “Towers” but “Paine” probably shouldn’t be translated into English as “Pain”—as in “Towers of Pain”—but translated using the native people’s word “paine” meaning “Blue.” And, yes, indeed, these granite towers are blue below the caps of ice and snow.

The peaks of Torres del Paine |

Below the peaks there is still much to see. There is some farmland, but also some protected grazing land where guanaco roam. These camelids which are native to this land are similar to llamas and vicuña and, to an extent, alpaca. These tend to stay in lower elevations than their cousins, the vicuña.

A farm and guanacos in Torres del Paine |

There are also rivers, waterfalls and lakes to draw one’s attention, but my eye always returned to the peaks.

Rivers, waterfalls and lakes in Parque Nacional Torres del Paine

Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, Torres del Paine, Chile |

Another way to sample the scene in Patagonia is from the edge by cruise ship which navigates into the fjords and channels of Chile. So we boarded the Norwegian Sun which took us into the entry to the Chilean Fjords and then treated us to a great sunset.

The cruise ship approach to seeing Patagonia |

When the channel broadened out, the view inspired a collective awe.

The view of the broadened channel

Being aboard ship also gave us the chance to visit a number of southernmost landmarks.

The southernmost point of land on the South American Continent is Cabo Froward. However, the collection of islands known as the Archipelago of Tierra del Fuego (Spanish for “Land of Fire”) is south of that. It hosts Ushuaia, the southernmost city in South America. The southernmost point of land in Tierra del Fuego is Cabo de Hornos - Cape Horn - where the Atlantic meets the Pacific and they both meet the Antarctic Ocean. We saw all three from the deck of our ship.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Cabo Froward |

|

Ushuaia |

|

Cape Horn |

|

We also stopped briefly at Magdalena Island in the Strait of Magellan, home to something in the neighborhood of 50,000 breeding pairs of penguins. The count fluctuates as the colony is still attempting to recover from the impact of a severe drought that killed off the vegetation that protected their burrows. They don’t seem to mind tourists, however. But park rangers insist you stay on the walkways and just look as the penguins strut their stuff or ignore their visitors.

The penguins of Magdalena Island |

After seeing so much grandeur from the surface level, I was confronted by the astonishing beauty of the land from yet a different perspective as we flew home. Looking down from 36,000 feet during a rare clear afternoon stretching nearly the length of the Patagonian portion of the Andes Mountains gave me, not just an aesthetic appreciation of the beauty, but an enhanced understanding of the geology involved. The flow of water and ice and the indomitable strength that stands against them while supporting them at the same time can almost be felt from this vantage point.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

| |

Brad Hathaway retired to live with his wife on a houseboat in Sausalito, California, after nearly two decades covering Theater in Washington, DC, on Broadway, and nationwide. A former vice chair of the American Theatre Critics Association he edits that association’s newsletter.

He's standing here before the Peaks of Torres del Paine. |

|

|

|

|