|

|

AMERICA'S FIRST COWPOKES |

|||

Story by Vicki Hoefling Andersen, images as indicated |

|||

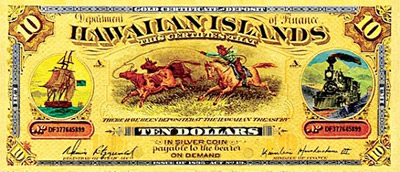

How did a place whose largest land mammal was the hoary bat until Polynesian settlers arrived with pigs about a thousand years ago, give rise to America’s first cowboys decades before they appeared in America’s Old West? In 1793, Captain George Vancouver arrived on Hawaii Island and presented seven long-horn cattle to King Kamehameha I. The King put a kapu on the bull and six cows forbidding anyone from killing them in the hopes they would thrive. Prosper they did and soon herds were stampeding through villages, trampling crops, destroying native vegetation, terrifying and even killing people. Eager to curry favor in these land masses recently “discovered” by the Western world, a passenger on an American merchant ship in 1803 gifted four horses to the King. They, too, began to roam the volcanic slopes, flourish on the rich vegetation, and multiply to join the thousands of cattle now roaming the landscape.

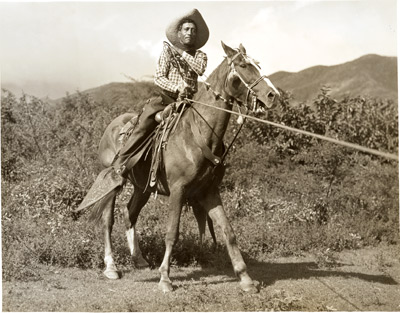

In 1809, smitten by its beauty, 19-year-old New England sailor John Palmer Parker jumped ship on Hawaii Island and was befriended by the King. By 1812 the cattle were out of control and the King allowed them to be captured, not an easy feat on foot. Parker became an advisor to the King, and in 1816 when he married the King’s granddaughter, Kipikane, was granted two acres of land in the northern portion of the Big Island and began domesticating the wild cattle and horses. This venture was the origin of Parker Ranch, largest in Hawaii and one of the oldest and largest in the U.S. Beef fat, rendered down into tallow and packed into casks, was exported for soap and candle production. Visiting whalers and traders purchased meat and hides. In the middle of the 19th century, Hawaii was exporting an average of 2,000 cattle hides a year. Local tanneries made use of tannin-rich native trees such as koa. Eventually cattle were shipped to feed the prospectors flooding into the California gold rush. Even by 1832 the Hawaiian cattle industry was booming and experienced help was desperately needed to manage what was approaching nearly 25,000 wild bovine. King Kamehameha III solicited help from experienced handlers in California, a part of Mexico at the time. Three vaqueros, Mexican cowboys, came and began teaching the Hawaiians how to handle horses and cattle. As they learned to rope, herd, fence and breed these animals, the Hawaiians also mastered stitching saddles, braiding 4-strand rawhide lariats and bullwhips, and making long bell spurs for their boots. They became known as paniolos, Hawaiian for “Espanol,” the language of the vaqueros. As the skills of the paniolos grew, they not only created a style of herding tailored to a tropical island, they shaped an amazing cowboy culture nearly a half-century before America’s cowboys hit the range.

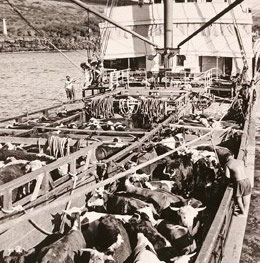

Getting cattle from pasture to port wasn’t so bad, but loading them onto the ships took daring, talent and panache. Hawaii Island was typical: cattle were driven into pens near the beach, then each steer lassoed and swum through the water to a shallow-draft boat called a lighter, used to transfer goods to and from moored ships. Once the cattle were lashed to the gunwales of the lighter, the boat would be rowed to the steamship where a paniolo would jump in the water, fasten a sling under the animal, and watch as it was hoisted onto the ship. It wasn’t until the 1950s cattle began to be loaded from a dock.

The Hawaiian saddle, known as a Noho Lio, was often specific to each island to fit the need of the rider for different types of topography.

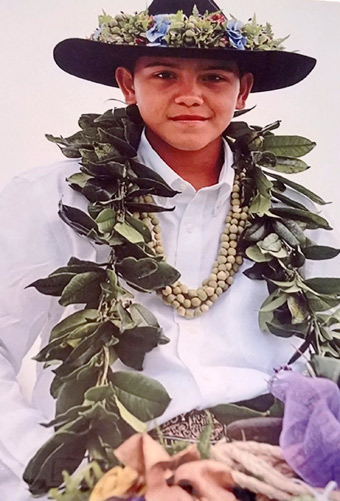

Paniolos adopted the vaqueros’ traditional work clothes: floppy wide-brimmed hats, colorful ponchos, bandanas, leather chaps and flat heeled heavy leather shoes. They added open-crowned hats woven from the leaves of the hala tree and routinely included a lei hatband. A new culture was emerging in the Islands, greatly enhanced by these home-grown cowhands.

What started as a way to anchor their headgear grew into another method of celebrating the beauty of their tropical home. Kimo Ho’opai Jr. dons an ice plant lei band, a much-loved choice by the end of the 19th century, while Charles “Kale” Stevens chose a lei of pansies. Paniolo from the G & C Freitas Ranch enter the arena for the Parker Ranch 59th Annual July 4th Rodeo sporting hats garlanded with the fragrant maile vine. Paniolos became well known for their hats adorned with lei bands. Not only were hat bands a practical way to keep hats on their heads in the wind, they were works of art and caught the attention of the girls. Most often made of flowers or greenery, shells and nuts were also used and even feathers were crafted into extravagantly beautiful pieces of art. Their horses also wore long and intricate lei for parades and rodeo shows. Along with their knowledge and equipment, the vaqueros brought their guitars. The paniolos quickly integrated them into Hawaii’s existing musical traditions resulting in a new and unique style of music. First the keys were “slackened” so cords could be played without fretting, a unique finger-picking approach to producing music on an acoustical instrument. Special tunings were developed, traditionally shared only among family and close friends, that produce the full reverberating sound of melody, rhythm, and bass. The paniolos allowed slack-key guitar to find its voice. About thirty years later the Portuguese arrived with their steel string guitars, and by the late 1880s, music from this instrument had captivated the Islands. The “steel guitar” as we know it today originated on Oahu in 1885 when teenager Joseph Kekuku laid his guitar across his lap and started experimenting with a railroad spike he had found, sliding it along the strings and plucking rather than strumming. Hawaii immediately took to this new sound and so did millions of others after its debut at the 1915 World’s Fair in San Francisco. Kekuku’s career as a world-touring guitar soloist took off.

Master guitar and ukulele luthiers, or builders, are found throughout Hawaii. Retailers such as Just ‘Ukes in Kailua-Kona’s Ali’i Gardens Marketplace offer a wide range of musical beauties, including a tenor piece made from moonlight ebony wood. Five Portuguese arrived on Oahu in 1879 with their small 4-string braguinha instruments. The Hawaiians christened the sound ukulele, "uku" for flea and “lele” for jump, in admiration of the musicians’ fingers quickly and skillfully capering up and down the neck. Easier to carry than a full- sized guitar, it quickly became a favorite for paniolos astride their horses, and popular throughout the Islands. By 1888, four of the five original Portuguese immigrants had their own ukulele shops. People were captivated by these tropical islands, newly annexed (“seized” to be historically correct) in 1898, and the sound of the Hawaiian steel guitar only added to the mystique and influenced various genres of American music. In the mid-teens Americans were purchasing 78 rpm vinyl records featuring the steel guitar or ukulele more than any other type of music. While the paniolos went about their work herding cattle and horses, embellishing their hats with lei and serenading the cattle with their ukuleles, Hawaiians had fallen love with the paniolo’s steed. Horseback riding became a favorite of the ali’i (royalty), women jaunting around the countryside astride their mounts rather than riding sidesaddle, much to the shock of Western sensibilities.

Some women placed fabric, known as pa’u (pah-oo) or a skirt, over their clothing to keep it clean as they rode. Originally nine to twelve yards of material was draped from the waist down, then kukui nuts were wound into the material and tucked into the waistband to hold it in place. The pa’u became a display of a woman’s heritage, then a fashion statement of their own. Today Pa’u Riders display their finery in parades and other special events.

Representing Kauai, Clancy Aku shows off Mokihana berry lei on his hat and draped around his neck; Kade Enic Kailihiwa Cox is proud to honor Lanai with a hat banded with native dodder and a lei of orange flowers. By the turn of the century each island became identified with a certain color and a particular flora for its lei, which Pa’u Riders and paniolo began honoring in their exhibitions: Hawaii Island: lehua flower & the color red

Grazing cattle is an important method of managing vast tracks of undeveloped land across the islands. With the variations in rainfall across each island, cattle can be moved into different areas as weather dictates.

According to the Hawaii Department of Agriculture, total value of cattle and calves production was approximately $48 million in 2021, the latest year for which statistics are available, making it the third most important commodity to the state’s economy. Hawaii Island accounts for nearly three-quarters of Hawaii’s cattle ranches (1,218 total in 2017), pasture land (765,579 total acres in 2020) and head of cattle (144,000 total in 2021). Over the years the huge ranches have broken up, and most now raise calves to ship to the mainland or process beef for local consumption.

Biggest in Hawaii and one of oldest and largest in the US, preceding many Texas and Southwestern ranches by more than three decades, Parker Ranch runs about 26,000 head of cattle on 130,000 acres spread between the Kohala Mountains and Maunakea in the northern portion of Hawaii Island. Starting from a humble two-acre plot in 1816, by 1847 the Palmer Parker family spread covered nearly 500,000 acres surrounding the town of Waimea. Horses were raised for the U.S. Calvary, and are still bred for speed and function on the Ranch. Other notable cattle breeders on Hawaii Island include the 11,000-acre Ponoholo Ranch and 8,500-acre Kahua Ranch in the North Kohala area. In the southern part of the island, Kahuku Ranch struggled for about 150 years to graze cattle on its lava-strewn land. Hawaii’s lava goddess Pele won out and in 2003 the Ranch became a unit of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Waimea (why-MAY-uh) is a vigorous and celebrated cowboy town situated on the southern slope of the Kohala Mountains, heart of Hawaii Island’s paniolo country and headquarters of Parker Ranch. It is also center of operations for the W.M. Keck Observatory and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope scientific teams thanks to the town’s proximity to Maunakea, home to 13 astronomical observatories. The residents of Waimea are a diverse group of paniolos, astronomers and scientists. Because there are towns named Waimea on Kauai and Oahu, this one is often referred to as Kamuela (ka-moo-EH-la), Hawaiian for Samuel in honor of Samuel Parker and his legendary hospitality. Kamuela is the official post office moniker. Maui’s cattle spreads include the 30,000-acre Haleakala Ranch and Ulupalakua Ranch’s more than 18,000 acres, both in Upcountry. Hana Ranch runs about 15,000 cattle on their 3,600-acre spread. Numerous cattle ranches still thrive on Kauai, Molokai and Oahu. Besides Kamuela, each island has at least one town that is still the heart of its paniolo culture and history although they may have evolved over time.

Maui’s paniolo continue to gather in the pastoral Upcountry town of Makawao (MAH-kah-wow) on the northern slopes of Haleakala. The region’s working ranches replete with cattle, horses and cowboys have been joined by orchid cultivators and a rum distillery. Komoda Bakery still serves up the drool-worthy malassadas they’ve been baking since 1916.

Paniolo life on Oahu centers around Waimanalo (why-mah-NA-loh) along the southeastern portion of the lush windward coast. The area is sometimes more recognizable as the site of “Robin's Nest” estate on the Magnum P.I. TV series, and home to Sea Life Park where Adam Sandler’s character, Henry, worked in the 2004 Adam Sandler/Drew Barrymore movie 50 First Dates.

As the early paniolo wrangled cattle through Hawaii’s rough surf to awaiting ships, they developed unexpected talents which made them stars in the rodeo arena, a sport still enjoyed across the state. Hawaii Island hosts rodeos at Parker Ranch, in Captain Cook and Hilo. Makawao has a paniolo parade and rodeo. Numerous rodeos on Oahu include one just for girls. Among the rodeo events are races, ranch mugging, dally team roping and barrel racing. Unique to Hawaiian rodeos are Wahine Mugging, where cowgirls round up a calf by its hind legs, and Po‘o wai u (see photos above).

There is always someone larger than life and whose fame carries on long after they are gone, and this is the case with Ikua Purdy, arguably the most celebrated of all paniolo. Great-grandson of John and Kipikane Palmer Parker, Ikua Purdy was born in 1873 in Waimea and by age ten was learning to ride and rope wild steer on the Ranch. Adept at breaking wild horses by tiring them out in the ocean, and gifted with the rope, he entered Hawaii’s first recorded paniolo contest in 1903. In 1907 the owner of a local ranch attended Frontier Days in Cheyenne, Wyoming, rodeo’s top proving grounds in those days. He realized Hawaii’s paniolos could beat the mainland boys, so the next year he sent his three top men -- brother Archie, half-brother Jack, and Purdy -- to Cheyenne. Decked out in vaquero-inspired clothing and chaps, hats adorned with flower lei, their colorful and unusual appearance wowed the 12,000 fans in attendance. What happened next stunned the crowd and made rodeo history. Purdy won the World’s Steer Roping Championship in a record-breaking 56 seconds flat. Archie came in second and Jack placed sixth. Against America’s best, the Hawaiian spirit and talent shone bright. In 1999 Purdy became the first Hawaiian inducted into the National Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame as well as the first inductee to the Oahu Cattlemen’s Association Paniolo Hall of Fame.

The cowboy/paniolo dream is still alive and strong in Hawaii. Keiki (children) dream of working with livestock and showing off their skills and perhaps some rodeo glory along the way, while grown-ups proudly display their passion in life. Footnote: In two instances for this story I have used the upside-down apostrophe or okina diacritical marking: ali’i (royalty) and pa’u (skirt) but have not done so for Hawai’i or the various island names, nor for ‘ukulele which should properly be proceeded by an okina. The Hawaiian language makes use of special symbols or diacritical markings which are crucial to proper spelling, pronunciation and meaning of Hawaiian words. Unfortunately most browsers don’t recognize them so they are otherwise omitted here. An okina indicates a small catch in the throat between vowels so the sounds don’t run together. A line above a vowel, or macron, indicates emphasis on that vowel. The use of diacritical markings can indicate the spelling of a word a name, noun, adjective, verb or adverb, and each of those can have clusters of meaning or implication depending on how it is used. One example is pau which means “finished,” but when macrons are added above the two vowels with an okina between them, it becomes “skirt,” specifically the garment worn by female horse riders. The spelling I have chosen for this story includes the okina shown as an apostrophe, but not the macron or line above the vowels. Another illustration is aina which, with an okina before the first “a,” means “eaten,” while an okina plus a macron over the first “a” means “land,” but if you leave out all diacritical markings it refers to “sexual intercourse.” As you can see, the proper diacritical markings can drastically change the meaning of a word. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|