Whale breaching near tour boat

| |

|

|

“The whales … are coming to touch us now using only the ways of grace -- acceptance, openness, play, peace -- reaching out to help us to awaken from the dream that we live alone on Earth.” From Eyes of the Wild: Journeys of Transformation by Eleanor O’Hanlon

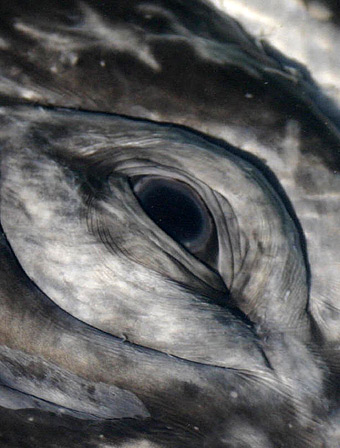

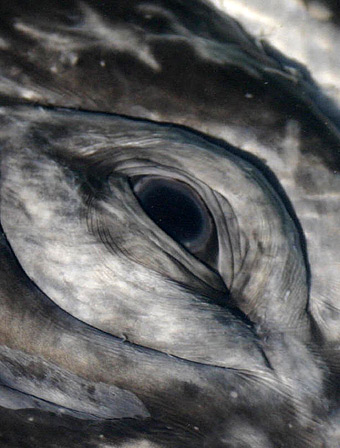

Have you ever looked a whale in the eye? If you have, you know how mystical it is. When you make eye contact, when the whale looks back at you, it is like bridging the gap between species because, after all, there is no separation -- we are one of all things. We are part of the great community of Earth.

One of the only places visitors can get up close and personal with a whale, perhaps even kiss a whale, is in Mexico, specifically the remote San Ignacio Lagoon on the Pacific side of Baja California Sur. Part of El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve UNESCO World Heritage site, it is Latin America’s largest nature preserve with 6.2 million acres of protected desert area created in 1988. |

|

| |

Here's Lookin` at You |

|

|

|

| |

In nearly all scenarios, touching wild animals is unethical. But in the Baja, the whales seek out human interaction. That interaction is carried out at the instigation of the whales, with their consent. They seem to know who humans are and respond differently than any other creature on Earth. Fortunately, encounters are closely monitored and numbers of visitors strictly controlled. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Whale bones arranged on a beach |

|

Gray whales seem particularly friendly in San Ignacio Lagoon. One popular theory is that because the inhabitants of the lagoons have always been fishing families, the whales became used to the presence of fishermen and formed close bonds with them. It was not uncommon for females to introduce their newly-born calves to the fishermen and, therefore, the next whale generation, and then the next, grew used to people. Or perhaps they came in peace, showing us how we can live in harmony.

In the late 1800s, numerous whaling expeditions found these quiet birthing lagoons, harpooning the Grays (and every other species) nearly to extinction -- and whales remember. So the fact that they come to the pangas (fishing boats) is in itself amazing. That they introduce their newborn calves to people is even more remarkable. No wild creature can make a greater gesture of trust.

Whales in Mexico's Baja are particularly friendly

Forty ton, 60 foot-long Pacific Gray Whales make the world's longest mammal migration, traveling 10,000-12,000 miles annually between their summer feeding grounds in the nutrient-rich, cold Arctic waters of Alaska’s Bering Sea and the sheltered warm winter calving lagoons in Baja, then swimming north again in the spring with their calves. By the end of the Arctic summer, the calves and mother whales separate and the mothers return to the warm lagoons to become impregnated again. Females, therefore, give birth every two years for the rest of their lives. Scientists estimate the average Grays live 70-80 years, so that is 30-35 calves over their lifetimes!

| |

My friends and I did a DIY trip. We made our (inexpensive) air arrangements between Guadalajara to La Paz (Loreto would have been a better choice, but schedules didn’t work with no direct flights), rented a car and drove half way there, staying overnight in a coastal town. The next morning we made our way over the Sierra de San Francisco mountain range to San Ignacio, a pueblo in the center of the date palm industry. The final 37 miles to the whale camp where we had booked three nights with Baja EcoTours, was an arduous, slow trek along the ever-changing sand road. (Recent improvements at water crossings have since made the trip a bit easier.) |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Driving to Eco BajaTours camp |

|

One of the reasons we chose Baja EcoTours was that they were the most remote of the dozen whaling camps on San Ignacio Lagoon, yet the closest to the designated whale watching area. Everything at Campo Cortez is solar and wind powered with small but rather substantial cabins rather than tents -- an excellent choice because the wind off the Pacific never stopped howling while we were there.

| |

|

|

Maldo Fischer is co-owner of Baja EcoTours. His family for many generations eked out a living fishing along the coast, but today his family runs the day-to-day lodge operations at the camp, serving as an example of how eco-tourism works as an alternative to commercial fishing. There is a domino effect of bringing jobs to locals as well as supporting businesses such as local ranching, fishing, and growing vegetables that supply much of the camp food. These people have a lifetime of knowledge living and working with the whales, so who better to take you out on expeditions. |

|

| |

Map of San Ignacio Lagoon and Campo Cortez location |

|

|

|

According to Maldo, touching a whale isn’t actually condoned by the Mexican government, it’s more of a loophole.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Pet a whale day |

|

Tourist reaching to pet the whale |

|

“When a government official several years ago came to inspect the operations of the local tour operators,” Maldo explained, “I took him out in my boat. For years the government said not to touch the whales and this official reminded me of that. But when a huge whale came alongside the boat, the official reached out and touched the whale.

| |

|

|

“’Don’t touch the whale!’ I said, but he responded that the whale came up to him. That moment changed everything.

"So now, if a boat is approached by a whale the boat has to stay still and touching isn’t mentioned in the law at all,” he laughed.

|

|

| |

On her side looking for attention |

|

Whales playing perhaps |

|

Whales glided through the water, their massive, powerful bodies rising and falling beneath the surface without a ripple. Just seeing their majesty was exhilarating. We could hear their explosive exhalations, we were soaked by the spray of their breath. We saw adults playing, we saw males competing for females -- which can turn into an orgy -- and mothers protecting and teaching their calves, perhaps the sweetest of all encounters.

The Baja also is a place where “spyhopping” is prevalent. Thrusting their barnacled bodies straight skyward and, balancing on their tails, the whales stop in midair to perhaps look around before sinking straight back beneath the surface. No one really knows why they do it.

Spyhopping Photo by Lorna Hill

Cetaceans hold the wisdom of the ages that is directly opposed to the greedy, egocentric mind that views Earth only as a resource. After seeing these whales so close, I understood as never before the madness of treating the Earth and its creatures as commodities to be traded and exploited. Thank you, whales, for the profound lesson.

Whale watching season is mid-December to mid-April, but best between January and March. Go to www.BajaEcotours.com for complete information on their whale camps.

Above and below Photo by Rodrigo Manterola

About the Author

| |

Diana Hunt started her travel writing career with the inflight magazine for Pan American World Airways. She worked her way up to editor of the magazine until it was sold, thereby launching her into the freelance travel business. She is a former member of The Aviation/Space Writers Association, The American Horse Publications, the North American Snowsports Journalists Association and the Carolina Nature Photographers Association. She has held various public relations positions and contributed to numerous equestrian publications.

Since moving to Mexico, she has been exploring her new home country, is an Associate Editor for Conecciones, a bi-lingual monthly magazine, and a member of the Artists Alliance of Lake Chapala. |

|

|

|

|