|

|

HE’E HOLUA: THE ANCIENT HAWAIIAN SPORT OF LAND SLEDDING |

|||

Story by Vicki Hoefling Andersen, images as noted |

|||

Picture the sport of “sledding” and most likely a snow-covered scene pops to mind: kids spinning about in plastic saucers and inner tubes, folks atop Flexi-Flyers and toboggans, the excitement of bobsleds and snowmobiling (which folks in many parts of the world refer to simply as “sledding”).

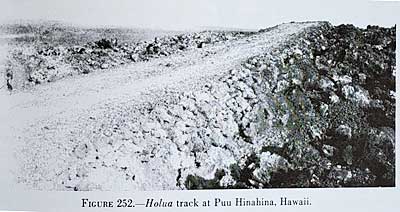

But let’s strip away the snow cover and get down to the land itself. Let’s cover it with rocks, and not just any chunks of cobblestone but hardened lava carefully placed atop an old lava flow. Now we’ve got a place to do some real land sledding! Variously referred to as land, lava or rock sliding or sledding, it was extreme and beloved by all ranks and genders of ancient Hawaiians. Big competitions were held among the ali’i (royalty). Women were great land sledding athletes and fierce competitors, although the missionaries who documented much of Hawaii’s history downplayed involvement by the fair sex. The missionaries did not like it at all, declaring it a heathen practice and a frivolous waste of time, and prohibited its continuation. A visitor witnessing an 1822 sledding competition near Kona provided one of the last documented accounts of the event. Let’s clarify a few terms to make following this story easier (no, there won’t be a test later): A quick note on the basic construction material—lava. The smooth, glassy-surfaced type of flow was called pahoehoe ("pah-hoy-hoy") by the ancient Hawaiians. Rock with a rough, “bubbly” surface was a’a (“ah-ah” – think the sound you’d make walking barefoot on it). These two names entered into scientific literature in the late 19th century and have become the designation volcanologists worldwide use to describe similar types of lava flow.

Research was a challenge – fewer than a dozen original sources even mention the sport in Hawaii, although there are stories of sleds in Polynesia most likely used to transport heavy loads. From traces of oral history, a few archaeological discoveries and the paltry amount of documentation he could find, Stone crafted a sled in 1994, headed to a point on the northern-most tip of Hawaii Island, and launched into his first ride. Later, after seeing an 800-year-old sled in a museum, he realized he had pretty much nailed it. According to Stone, it was definitely a competitive sport but also a way to honor Pele, the Polynesian Fire Goddess who gave birth to the Hawaiian Islands. Venerated for her talent in he’e holua, all the slides were located on old lava flows. Riding these flows was both a way to pay tribute to Pele and to triumph over her potential rage. There was significant protocol to the occasion, and large slides near important heiau may have involved sacred rites. “All rock slides were associated with and constructed around heiau. Each heiau I found included a slide,” Stone informed me. “They were always in conjunction with a slide.”

Many stories point to Pele’s love of this sport and it was the cornerstone of a well-known Hawaiian legend of why Maunakea no longer erupts. Poliʻahu, the Snow Goddess who lived on Maunakea, was sledding with three friends on the slopes of her mountain when they were approached by a woman who asked if she could join the competition. The stranger was described as “flying fire” during the descent, but Poliʻahu won the race. The stranger became furious and caused the ground to violently tremble, revealing herself to be Pele, the Fire Goddess and Poli’ahu’s sister. Pele hurled her holua into the ground causing cracks in the mountain which allowed smoke and fire to bellow forth. As Pele’s eruptions continued, Poliʻahu fled up her mountain and threw a mantle of snow over the summit, cooling the molten rock. Pele succeeded in destroying the holua slide but conceded defeat and returned to her home at Kilauea, never again breathing life into Maunakea.

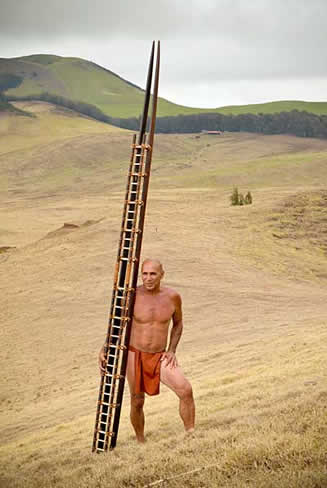

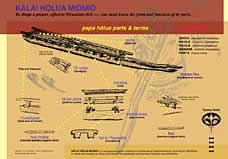

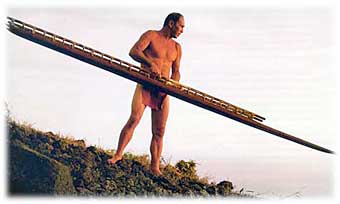

A papa holua was about 5-6 inches wide, 4 inches high and 12-14 feet long. Carved of hard, dense native wood like kailua or ohia, it weighed upwards of 50 pounds. A pair of runners, connected by crosspieces, were designed to flex during the ride. A pair of smaller rails atop the cross members, wrapped in kapa cloth, served as a small platform. Coconut fiber or the native bush olona were used as cordage to bind the parts, and the frame was covered in lauhala matting. Even after years of creating papa holua, Stone says it takes him about 27 hours to complete one.

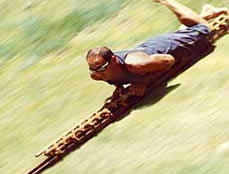

Two basic techniques were used to achieve the goal of sliding as far as possible or being faster than your competition. The rider could stand sideways and, much like a snowboarder, kick with one foot to get going then put both feet on the sled. Or they could take a few running steps holding their sled in front of them, launch themselves onto the sled chest-down, and hold tight to the handgrips as though life and limb depended on it. Regardless of chosen style, a fair amount of body balance was needed to steer the sled, essential since some courses included curves. The sled runners were well-lubricated with kukui (candlenut) oil to reduce friction, and as the sun baked the lava rock, riders could reach ticket-on-the-interstate speeds of 70mph. Stone told me, “The act [of he’e holua] was a form of sacrifice in itself.” I didn’t ask for details when he mentioned some of his injuries which included surgery after “tearing off” his face, an 18-inch rip in his thigh, In an interview with Outside Magazine Stone understatedly admitted, “We’ve gotten up to 50 miles per hour. At that speed, it’s pretty horrendous if you eat it.” He believes grass slides were used to hone their skills. Man-made and natural holua slides were plentiful throughout the state, and of the 82 kahua identified so far, the majority are found on Hawaii Island (“The Big Isle”). Stone has uncovered more than four dozen himself but hinted to me with a note of excitement, “There are lots more remnants of slides to be found.” Each holua had its own name and came in varying lengths. Like a toboggan course on super-steroids, the natural terrain was customized with protruding stumps and rocks, walled troughs, hair-raising plunges and other such perils. Particularly long slides were built for speed and engineered with slight turns and wavy pitches to make the ride even more challenging. Construction of a slide began with slabs of pahoehoe lava rock, then filled in with various-sized a’a boulders and stones, packed with dirt and a final cover of pili grass or perhaps thatched mats or ti leaves. Each holua was unique and constructed to different specifications. Some accommodated a single papa holua, others were wide enough to accommodate six side-by-side contenders.

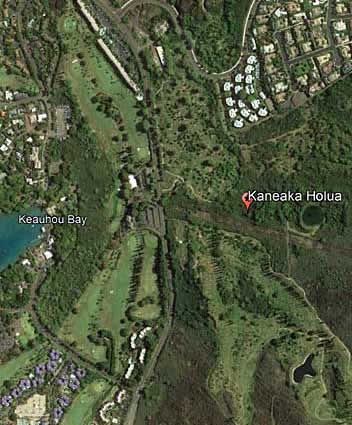

A few miles and 1400-feet up Hualalai volcano from Kailua-Kona sits the village of Holualoa, its name (“long slide”) honoring perhaps the most famous of all remaining holua slides and whose track wends its way downslope through the area. Properly called the Kaneaka Holua Slide, it is popularly referred to as the Keauhou Slide due to its location. Largest and one of the most-studied and well-preserved holua in the State, it originally twisted and plummeted like a double-black diamond trail over 4,000 feet down the mountain to the shore of He’eia Bay. With the passage of time, the upper and lower portions have been lost, destroyed or developed, but a track about 1,290 feet long by 50 feet wide is still evident.

A small portion of the Kaneaka Holua shows up in dramatic contrast to the surrounding landscape in the aerial image above left. Slide is dead-center in picture, just to the right of the reservoir towards the top of the picture. (Image courtesy Holualoa Inn) The GoogleEarth shot shows the direction the slide took towards He’eia Bay.

Oral histories speak of Kaneaka having been built in 1814 by Kamehameha the Great to honor the birth of his son Kauikeaouli (later King Kamehameha III), who was born at Keauhou. By reconstructing a section of the track, Stone said in an interview for National Geographic’s travel website, he theorizes that 2,500 people would have labored for six years to build the slide. In 1917, Henry Walsworth Kinney published The Island of Hawaii, a guidebook to the land, historical events, cultural traditions and locations. He said of the Keauhou slide, “Mauka [toward the mountain] of the village is seen the most famous holua in the Islands, a wide road-like stretch, which was laid with grass steeped in kukui-nut oil so as to allow the prince and his friends to coast down in their sleighs constructed for the purpose.” In the mid-20th Century, Henry E.P. Kekahuna, a talented Hawaiian surveyor working for the Bishop Museum, mapped over sixty heiau and accompanying holua slides across the Hawaiian islands including Keauhou. “The starting point is a narrow platform paved level, succeeded by a slightly declined crosswise platform 36-feet long by 29-feet wide, and is followed by a series of steep descents that gave high speed to the holua sleds... Great care seems to have been exercised in the building of this huge relic of the ancients. Practically the whole slide is constructed of fairly large ‘a‘a rocks filled in with rocks of medium and small-sized ‘a‘a. The base walls on the north and south vary in height according to the contour of the land. The width of the runway varies considerably... The length of the slide, measured through the middle from the present lower end, is 3,682-feet. It may have extended about 3,000-feet farther, as it is said that in ancient days the now missing lower part extended along the point north of Keauhou Bay to He`eia Bay.”

There are three slides at Puuhonua O Honaunau National Historical Park, aka “Place of Refuge.” The best views of the first two are from the “1871 Trail” which originally linked coastal villages along the South Kona Coast.

Other holua kahua in the islands included one on Kauai where two slides cross each other on a hill northwest of Koloa.

The Reverend Hiram Bingham, who brought the first company of missionaries to Hawai'i in 1820, provided a descriptive account of he’e holua: “In the presence of the multitude, the player takes in both hands, his long, very narrow and light built sled, made for this purpose alone, the curved ends of the runners being upward and forward, as he holds it, to begin the race. Standing erect, at first, a little back from the head of the prepared slippery path, he runs a few rods to it, to acquire the greatest momentum, carrying his sled, then pitches himself, head foremost, down the declivity, dexterously throwing his body, full length, upon his vehicle, as on a surf board. The sled, keeping its rail or grassway, courses with velocity down the steep, and passes off into the plain, bearing its proud, but prone and headlong rider, who scarcely values his neck more than the prize at stake.” Tom Stone’s nickname, “Pohaku”, means “stone” in Hawaiian and by extension the foundation of a house. Very appropriate for a man working to strengthen and bolster the base of Native Hawaiian customs. His Kanalu non-profit organization promotes the sport with the mission statement: “To pursue, perpetuate, reinstitute, and revitalize our cultural traditions.” Stone has been hand-carving surfboards since 1978, and his Hawaiian Boarding Company provides Pohaku-crafted surfboards and papa holua. He spent a decade as Hawaiian Studies professor at the University of Hawai'I Manoa and Kapi'olani Community College, and was Cultural Advisor to Turtle Bay Resort. Years as a champion surfer and windsurfer, Stone also served more than 15 years as an Ocean Safety Officer and District Captain for the City and County of Honolulu. In 2012 he was invited to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian for a public demonstration of carving a traditional Hawaiian surfboard and lashing together a papa holua. I invited “Pohaku,” if he was back on his Native island sometime this winter, to do some sliding together on Maunakea. That would be on Poliʻahu’s snow, not Pele’s lava. For more information: ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|