|

|

THE ARCTIC ARC — PART 2 |

|||

Checking Out Iceland and Greenland |

|||

Story and photos by Brad Hathaway |

Last time, we explored the eastern half of what I call the Arctic Arc. We found that there was more to fascinate and thrill in Norway than just waterfalls, glaciers and fjords. Now it was time to travel to the western portion of the Arc: Iceland and Greenland. These two countries share a common history with Norway as they were settled by Vikings nearly twelve centuries ago. The very name Viking is a derivative of the Norwegian word “vik” meaning someone who came from the fjords. And, famously, it was the Viking desire to discourage people from coming to the lovely green land they had settled that made them call it “Iceland”—while they didn’t mind if settlers tried to find spots not covered by the ice shelf of the larger ice-covered island, so they called it “Greenland.” At least, that’s the favorite version of the story—there’s no real proof of the who and why for the first naming of these lands. The truth is obscured by the mists of history. What is generally known is that Vikings began to arrive in Greenland in the 70s…the 870s that is.

In 1972, in the midst of the cold war, the world chess champion, Russian Boris Spassky, and American challenger, Bobby Fischer, matched wits in Reykjavik, the capital city of Iceland. That may have been the moment when the world first focused on this beautiful, rugged and unique nation. But then, in 1986, it was back in the news as US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union General Secretary of the Communist Party, Mikhail Gorbachev, held a summit in Reykjavik. That summit failed to achieve the elimination of nuclear weapons or ballistic missiles that was its goal, but it laid the foundation for future successful negotiations. Then, again, the world’s focus was on Iceland in 2010 when one of the relatively small nation’s 130 volcanoes, the mouthfully-named Eyjafjallajökull, erupted spewing ash as high as seven miles into the jet stream. That stream distributed the ash over much of Europe and many countries had to ground all air transport because the ash, if ingested into jet engines, could stop them from working. Iceland is a free-market, capitalist nation with a strong welfare system and a notably even distribution of income. Its Gross National Product Per Capita of over $52,000 ranks #25 among 229 countries of the world, while the equality of its distribution among all families is better than all but eight. Our visit began in the northern municipality of Akureyri, home to just under 20,000 Icelanders. Our very first discovery was an example of fine architecture in service of cultural activities that seems to be remarkably typical of Nordic countries—the HoF Cultural and Conference Center, home for the North Iceland Symphony Orchestra, the TonAk School of Music and conference facilities. Designed by the architecture firm Arkþing, its exterior is a huge disc of Icelandic igneous rock which belies the warmth of its wood paneled interior.

Exterior and interior of the HoF Cultural and Conference Center in Akureyri

It wasn’t the only notable building in Akureyri, however. We were impressed by its church on the hill overlooking the city and by the recently enlarged library which is notable for a town of this size.

A distinct feature of life in Iceland is the use of geothermal resources to heat buildings, as a utility elsewhere might supply natural gas or even electricity, which are also abundantly available in all of Iceland. The Earth’s geothermal heat which is deep below the surface is closer to the surface here, and also feeds spas and warm-water swimming pools which can be found in almost every community. This is where much of the daily business of the municipality is quietly done amongst the townspeople as they take their daily soak in the thermal waters. We stopped at one of these pools during our tour.

The phenomenon of such accessible geothermal warmth is a result of Iceland’s location straddling the line where North America’s tectonic plate meets the Eurasian Plate. Indeed, you can walk down into the ravine created by that juncture in Thingvellir National Park with the edge of North America forming a cliff on one side of you and the flat lands of Eurasia on the other.

The meeting of the tectonic plates also leads to spots where rivers fall over cliffs and into ravines making Iceland a place where you can view many awe-inspiring, gut-sucking waterfalls. The Godafoss waterfall in Northern Iceland, pours the water of the Skjálfandafljót River over a cliff 40 feet high and over 100 feet wide. Its name comes from the story that, in the year 1000, when the lawspeaker Thorkelsson proclaimed the Christian religion, he threw the graven images of the Norse gods over the falls. After that plunge, the river continues down the gorge to plunge even further. Near Reykjavik in the south, the Gullfoss or “golden waterfall” on the Hvítá River also has two stages of its decent. First a drop of about 35 feet deposits the river into a narrower passage from which the torrent tumbles another 75 or 80 feet.

Much of the land of Iceland is open pasture and scrub. Often, the land sports the gobbígobb (sounds like “goppy gop”)—Iceland’s iconic horses. They are unique in that they have one or two more gaits than most other horses. Most horses can walk, trot and gallop but Icelandic horses can tölt (a smooth, fast gait) and some also skeid, which is a “flying pace.”

Often, these horses coexist with the sheep which are raised principally for their meat and their wool. While the population of Icelandic Sheep has declined in the 21st Century, it is still true that there are more sheep than people in Iceland. These sheep were originally introduced to Iceland by Vikings in the late ninth or early tenth century and have prospered on the island.

While it remains part of the Kingdom of Denmark, and the official chief of state is Denmark’s Queen Margretthe II, the head of government is Greenland Premier Mute B. Egede, and domestic laws are enacted by the unicameral Greenland Parliament. Denmark, however, continues to control a number of policy areas for Greenland including foreign affairs, finance and security. Had then-President Donald Trump actually tried to purchase Greenland, it isn’t at all clear from whom he would have purchased it. The last of the Arctic Arc to be settled by Europeans, Greenland is geographically huge. Its total area is over three times the size of Texas; however its arable land is just a few thousand acres. This is a land to visit on its edges and most of that should be done by ship as there aren’t paved roads from town to town or inlet to inlet. In fact, all the roads in the country total less than 100 miles and only about half of them are paved. Instead, Greenlanders tend to rely on snowmobiles, airplanes and dog sleds. I’m told, however, that the capital city of Nuuk does have two traffic lights. There is also the US Space Force base at Thule with a 10,000-foot runway on the northwestern extreme coast—but, only about 600 people live there year-round. One hundred and forty are Americans. We didn’t visit the ice sheet but here’s a stunning photo of icy Greenland from NASA.

Greenland’s national theatre is based in Nuuk but does a lot of touring to communities within the country. It also takes performances abroad to share a touch of Greenland culture with the world. Here’s a photo of one of their performances, a piece based on the book “Those Who Run in the Sky” or, “Angakkussaq.”

Our visit began with a stop at Qaqortoq, a village of 3,000 near the southernmost edge of the island. Its multi-colored buildings are typical of Greenland communities, drawing off a colorful tradition from colonial times when the color of a building indicated its use: red indicated a teacher or a minister, green a mechanic, blue a fishermen and yellow a nurse or doctor.

In the center of town you can find the oldest public fountain in Greenland, the Mindebrønden. To be totally accurate, however, this should be characterized as the “older” public fountain in Greenland as there are only two.

It is surrounded by some of the town’s paved roadway. I’m afraid I wasn’t able to pronounce the name of the street - Tassuunnaqquunnerit Tamaasa.

Among the sights during a visit to Qaqortoq were the open-air fish market (fishing is Greenland’s major industry, accounting for nearly 90% of its exports) and the open-air art exhibit, “Stone & Man.” This art exhibit features some 24 sculptural pieces carved into the exposed rock of the cliffs and boulders in the town.

But it was the glories of natural scenery that drew us to Greenland and the sights were spectacular. We cruised through Ikerasassuaq, or, as it is called in Danish, Prins Christian Sund - the English is a simple Prince Christian Sound. It is a “sound” rather than a “fjord” because it is open at both ends and, therefore, ships can transit one way and not have to retrace their route to get back to open water. The Christian in question here is Christian VIII who was a Danish prince from 1786 to 1839 and then King until his death in 1848. At dawn we reached the entry to the sound where we could see icebergs floating out to sea.

The sound is a 60 mile passage through some of the most splendid scenery at the southern tip of Greenland - but even here you won’t see a lot of green. The mountains on either side of the sound are mostly bare rock.

The sound is so narrow that at some points the shadows of the mountains of one side are etched on the slopes on the other.

Water falls, abound as well.

Sometimes, waterfalls and icebergs fuse.

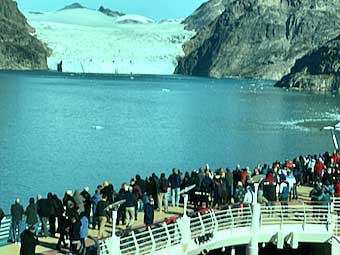

The sound gave us a chance to get up close to a glacier.

Which, of course, brought all the passengers on our cruise ship fusing to the deck to take photos.

Then our ship took its leave of the sound and headed south, out of the Arctic Arc.

Admittedly, our trip was but a “sampler” with a bit of Norway, a bit of Iceland and a bit of Greenland. It left us with the hope of a more lengthy return - perhaps a visit in the season of the glorious Aurora Borealis. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|