|

|

FINDING BEAUTY AT HART MOUNTAIN |

|||

‘This is a Land to Possess and Embrace’ |

|||

Story by Lee Juillerat, Photos by Lee Juillerat and Liane Venzke |

We spent the morning marveling at the astonishing beauty and diversity of seasonal wildflowers - and that afternoon, embracing the preserved evidence of a distant past.

Liane Venzke and I were camping at the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in southeastern Oregon. Hart Mountain is a place I’ve visited many times over the decades; but even after years of poking about, there’s always something new to see and appreciate.

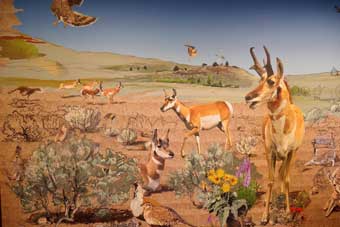

In his 1960 book, “My Wilderness: The Pacific West,” U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas wrote that Hart Mountain “rises like a gargantuan loaf from dry prairies of southeastern Oregon.” The expansive refuge, which spans more than 422 square miles, was created in 1936 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to serve “as a range and breeding ground for the antelope (pronghorn) and other species of wildlife.”

I’ve seen herds of pronghorn, critters that some people mistake for deer, many times at Hart Mountain. North America’s fastest land animal, they can run at speeds upwards of 60 mph. Pronghorns are deservedly the refuge’s celebrated species. But Hart Mountain isn’t just about pronghorns. Game biologists say there are more than 300 species of wildlife, most notably California bighorn sheep, greater sage grouse, mule deer and a wide diversity of birds, including killdeer, Canada geese, avocets, red-naped sapsuckers and more.

The search for petroglyphs came after a morning hiking the old Barnhardi Road to the Barnhardi Basin. The road, then still seasonally closed to motor vehicles, passes mostly through the wide-open expanses offering a coloring box array of flowers - paintbrush, corn lilies, arrowleaf balsamroot, woolly groundsel, showy penstemon, waterleaf, longleaf phlox, lovage, western blue flax, elk thistle, larkspur, wild buckwheat, false hellebore and much, much more. Frequent, too, were a variety of shrubs - wax currant, antelope bitterbrush, mountain snowberry, rabbitbrush, little-leaf horsebrush and sprawling fields of big sagebrush.

Although most of the area we hiked is above timberline, there were occasional stands of mountain mahogany, western juniper and, along areas of Rock Creek, proliferations of water-loving quaking aspens.

After returning to our campsite near the hot springs, we drove back to and past the Refuge headquarters. About a mile west of headquarters we parked at a locked gate by a “Petroglyph Lake” sign. For years it was possible to drive about 1-1/2-miles on the gravel road to a parking area. The road was closed several years ago but remains open to hikers, bikers and equestrians.

The road ends at Petroglyph Lake, but the true destination are the petroglyphs themselves, which are located on the basalt cliffs above the lake’s west shore. The petroglyphs - petro meaning stone or rock and glyph meaning to carve – were likely created more than 10,000 years ago. The long-ago paintings include animalistic figures, unusual configurations, and stick-like “people.” Actually, this location of the petroglyphs above Petroglyph Lake is just one of the many places on and near the Refuge and throughout southeastern Oregon where the ancient rock art can be found.

The genesis of petroglyphs evokes speculation. As one “expert” wrote, “Because modern Oregon tribes have no similar painting traditions or legends, the petroglyphs may well be the work of a different people—a mysterious, earlier culture that hoped to communicate with the spirit world through symbolic messages at sacred sites. One of those sacred places must have been this small lake on the vast desert plateau atop Poker Jim Ridge. In what is now the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge, nearly 100 drawings decorate the basalt ledge ringing Petroglyph Lake’s western shore.”

From the path that borders the lake, we followed a little-used trail up to the cliffs. We were quickly rewarded, finding dozens of petroglyphs, some in groups of a half-dozen or more, others by themselves along the walls. Some of the images were weathered and faint. Some were abstract leave-it-to-your-imagination figures. Others were drawn in geometric designs. It’s believed some are animals that were hunted for food while others might represent the spirit world. At Petroglyph Lake as elsewhere, some believe the petroglyphs may have no mystical meaning but, less romantically, are a prehistoric form of graffiti. Whatever is true, they are the stuff of fascination and imagination.

We followed the faint path along the rim rocks and rock outcrops, some colored with lichen, finding more and more petroglyphs. Some were in the shape of pronghorn, others were stick-like people with several in wriggly forms. Two side-by-side figures seemed to have their arms joyfully reaching out. Another had an owl-like face. Yet another appeared to be a person falling forever down-down-down. Others resembled circular bullseyes. Among the most distinct and preserved is what might be imagined as a giant four-legged bug or critter.

I’ve made several visits to the site, but this time, with patience and a partner willing to shimmy around rocks and keep searching, I saw more petroglyphs than on any previous outing. We didn’t count how many, but estimate we viewed 50 or 60 or more.

Importantly, we looked but didn’t touch. Even the touch of a hand or finger could cause damage.

Soaking in the hot springs proved a fitting ending to our day. We had experienced what Justice Douglas experienced more than 70 years earlier. As he wrote of Hart Mountain, “This is a land to possess and embrace. It is a land to command as far as the eye can see.”

About the Author

|