| |

For a week I had enjoyed the seaside activities of Puerto La Cruz – one of Venezuela’s top Caribbean resorts. I had been seduced by its touristic attributes, especially the crystal-clear waters of the tiny nearby beaches that are part of the Mochima National Park. Dreaming of these earthly Edens, I was awakened by the ringing of my telephone. I looked at my watch. It was 5 a.m.

“Wake up! We must be at the car rental agency by 7, and I must have my breakfast before we leave for the Guácharo Cave.” It was my vacation-met Canadian friend who had, on numerous occasions, informed me that he could not operate without three meals a day. Now, he was making sure that I would be ready in order that he may have his breakfast. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

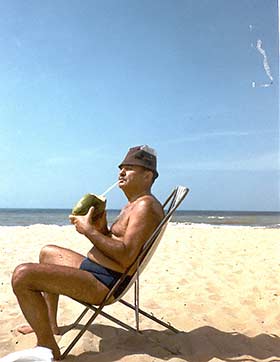

Author relaxing on a Guácharo beach |

|

It was a little after 6 when the taxi let me and my friend, Ralph, and his wife, Rose, off at Paseo Colon – Puerto La Cruz’s main thoroughfare. Alas! There was not one restaurant open.

By 7, we had taken possession of our Chevette Junior and were on our way along the coastal highway, heading toward Cumaná – 80 km (50 MI) to the east. My friend seemed gloomy. “Don’t worry! We will stop on the way for breakfast.” I was trying to sooth Ralph’s feelings after the fruitless one-hour search for a restaurant.

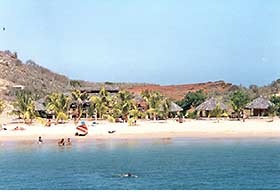

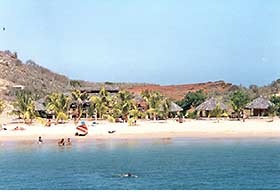

Playa Colorado

Soon, we passed Playas Arapito and Vellecito, then turned and stopped at Playa Colorado – the most appealing of the three beaches. Its roan coloured palm-covered sands, contrasting with the turquoise hue of the waters gave it a unique character. The atmosphere was tranquil. It was early and the usual beverage, food and souvenir vendors were absent. The moments we spent on this gem of a beach, surveying its sands, were memorable – that is, if one overlooked the littered landscape.

Back on the mountainous road, the highway snaked its way through Mochima National Park, which incorporates some of the most beautiful coastal scenery in Venezuela. At the crest of a high point we stopped awhile to savour the spectacular view of jutting peninsulas and islands set in a sea mirroring the early morning rays of the sun.

Guácharo - Mochima National Park Beach

Back in the early 1990s, I had travelled the same road we were driving on today. Like this trip, the traffic-laden road had then twisted on and on, past shack after shack of the poorest dwellings that I had ever come across. On my previous trip when I did not see one decent home, it was apparent that the oil wealth of Venezuela was not, at that time, doing much good for the poor. According to a Venezuelan - whom I met in Puerto La Cruz when I had first travelled there - if the government had allotted 10 million for a project, 9 million would have disappeared along the way. On this ride, I did notice notable improvement, but still far from what a tourist from a first-world country would find as comfort.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Puerto la Cruz, Colon, Venezuela |

|

Puerto la Cruz, Colon, Venezuela |

|

Along both sides of the highway there were endless people waiting for transportation, washing their clothing or hair, promenading while their children played on one of the busiest highways in Venezuela. The road was used as a sidewalk. It seemed that no one had ever heard of traffic accidents. Amid these human activities, chickens, goats, donkeys, horses and pigs were feeding. For travellers, there were countless country restaurants and food stands, edging the highway – all of them unappealing to most tourists.

On the way to Guácharo Cave

Have you forgotten? I must have my breakfast!” Ralph, at the wheel, sounded somewhat peeved when I said, “If we drive without stopping, we will reach Cumaná in less than an hour.” Seeing that he was at the point of being furious, I pointed to one of the restaurants by the wayside. Ralph glared at me and exclaimed, “Can’t you see how dirty it looks?” “But! But! You can eat barbecued fish, fresh from the sea. It makes no difference what the place looks like.” I was thinking of a Mexican cook in Acapulco, who had become disillusioned with North Americans, telling me, “We are cleaner when cooking for our own people than for tourists. To tell you the truth, we are not enamoured with their arrogance and wealth.” “We will eat in Cumaná.” Rose, a very quiet person, had decided that there would be no touristic restaurants before reaching that historic town.

Eight km (5 MI) before Cumaná we were driving on a four-lane highway, a completed part of an autostrat from Caracas, the country’s capital, to the eastern provinces. After years of work, only small sections of this highway have been finished and it was much improved from the first time I had travelled it. We then entered Cumaná – the oldest Hispanic city in South America.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Straddling the Manzanares River on both banks, and just below the tourist isle of Margarita, this town of 270,000 is the capital of Sucre State and recalls the heritage of the continent’s first settlement, dating back to 1521. From the past, it retains the restored Castillo of San Antonio, a fortified castle with a panoramic view of the old city, ocean and surrounding countryside, and the old church of Santa Inés which edges narrow streets and ancient colonial homes.

Apparently, Ralph had momentarily forgotten about his illusive breakfast. When I suggested that we explore the old town before eating, he did not object. After a quick tour, by 11 o’clock we were sitting down in an Italian restaurant. But alas! There were no bacon and eggs, Ralph’s epitome of breakfasts. After grudgingly agreeing to consume fried fish, my friends left for the washrooms. In a few minutes they were back. Angrily, Ralph sputtered, “They call this a restaurant? There’s not one drop of water in the taps.” Rose smiled. She seemed to take the hazards of the road in her stride. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Church of Santa Inez in Cumana |

|

The food was tasty and, even though it was belated, Ralph had had his meal. He now looked happier than he had all morning as we left Cumaná on our way eastward on a continuing winding coastal road. To one side, looking down to the sea, were the tiny beaches on the rich fish-breeding waters along the Gulf of Cariaco: on the other, rolling hills, green with trees and shrubs and, like those before Cumaná, seemingly uninhabited.

For the first time since I reached Venezuela, the day was not clear. Foggy mist covered parts of the road. Past Marigūtar, where people paint bright murals on their homes, the road wound on until about 160 km (100 MI) east of Puerto La Cruz where we turned southward. The highway became narrower and much more winding as we made our way through the lush coastal hills – part of the Turimiquire Mountain range. It was a jungle-like landscape, made glistening by a light rain caressing the leaves. Every turn was scarier than the next, but the fact that there were very few cars on the road allayed, to some extent, my apprehensions.

The countryside, except for a few huts, appeared to be uninhabited until about 40 km (25 MI) from the coastal road. Men and women could be seen working in small fields of bananas, oranges and other fruits. A short distance before the town of Caripe, we turned to the right and in a few minutes were parked before the ‘Cueva del Guácharo (Guácharo Cave) – a Venezuelan monument which has been declared a world sanctuary.

| |

|

|

|

|

The naturalist, Baron Alexander Von Humboldt discovered the cave in 1799 and found that it was inhabited by thousands of oilbirds, known as guácharos. In the subsequent years, their nests were harvested by both Indians and missionaries for the fat of the birds which was then rendered into lighting oil – hence their name oilbirds. Today, they number about 18,000 – far fewer than when Humboldt stumbled on the cave.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Guácharo Cave entrance |

|

Baron Alexander Von Humboldt |

|

A large night-flying relative to the whippoorwill, the sightless guácharos have a wingspan of over three feet. At dusk, every night, they fly out using a built-in radar system for flight. Near 4 a.m. at dawn, they return with their pouches full of palm and laurel fruit, navigating their location by rapid-fire clicks.

We took a guide with a lantern, and then entered the Guácharo Cave – a 10 km (6 MI) tunnel of majestic halls and deep galleries. The first hall about 40 m (130 FT) high and 448 m (1470 FT) long is the home of the speckled reddish-brown guácharos. Editor's note: Photos of oilbirds, the guácharos, can be seen here.

As we made our way on a slimy path alongside a clear stream, the guide pointed to crabs, blind pink fish, sightless large mice and numerous insects in and along the edge of the water. All around, the stalactite and stalagmite formations took on animal and human shapes. As we passed these forms, the guide pointed and indicated that it was a saint or bear or dolphin head, etc. I was looking at one of these shapes, while listening to the deep groans of the disturbed guácharos, when I stepped into a deep muck of bird droppings. I cursed my luck and moved on, feeling the slime inside my boots. At the 1 1/2 km (1 MI) depth, to where most visitors are usually taken, we turned back. Outside, as I washed my boots in a stream, I reminisced about this impressive cave with its eerie shapes and sounds.

Leaving the strange home of blind birds, we retraced our steps. Darkness closed around us about 50 km (31 MI) before Puerto La Cruz. Driving became very difficult. The curving mountain road, speeding autos, cars without headlights and others without brake lights made driving nerve-wracking. Ralph pushed our tiny, fragile Chevette. “Why are you rushing?” I was fearful of an accident. “We must get to the rental agency before it closes.” My friend was not very talkative. I thought to myself, “Is he thinking of returning the auto? More likely, of his delayed dinner.”

In any case, all went well and at 9 p.m. we were having a fine Chinese meal in Puerto La Cruz. Savouring his chicken and almonds, Ralph turned to me, “I forgive you for making me miss a meal. This makes up for it.”

I, too, was content. The food was heavenly, but my thoughts were about our 450 km (280 MI) trip from the pleasures of Puerto La Cruz, through a fantastically beautiful countryside, to the cave of strange birds – a wonderful and unique experience of beautiful beaches, dark caves and oilbirds, all this with a travelling companion who successfully survived on two meals a day.

Habeeb Salloum M.S.M.

|

|

|