CURLY'S CABOOSE

|

Editor’s note: CURLY'S CABOOSE While the caboose belongs on a freight train, who among us passenger train enthusiasts doesn’t have a fond memory of this vanished railroad icon? A caboose, positioned like a red steel sculpture, is the centerpiece of a small shopping plaza in O'Brien, Oregon. Painted in the glistening colors of its former home railroad in McCloud, California, across the Siskiyou Mountains, it provides a cozy office for the owner of the small business that it headquarters. Had this proprietor dreamed for years of settling down in some small town to do business out of a caboose? If so, that dream is shared by many Americans who spend hard-earned dollars to find, purchase, and move retired railroad cabooses to their property, often many miles from the nearest rail line.

This colorful scene brought back pleasant childhood memories of the caboose on American railroads. In the 1940s I considered myself fortunate live in Ambridge, Pennsylvania, headquarters of the American Bridge Company, fabricators of the massive steel truss segments of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, which were shipped across the country to Oakland, California, on Pennsylvania Railroad flatcars.

I grew up living in a row apartment house just a few steps away from a Pennsylvania Railroad industrial branch line which serviced the steel fabrication industries of Ambridge. At the peak of the American industrial era, with the mills working 24/7, we had the opportunity to wave at the crew of the steam switch-engine (or "shifter") and caboose that came to town twice a day, every day, transferring freight cars to and from nearby Conway Yards.

My father, who was employed in the shipping office of the H.H. Robertson Co. nearby, knew the switch engine crews well. For the forty years he worked there, he created packing bills for countless carloads of steel roofing, wall panels, and industrial ventilators that left the loading docks of Robertson's. So when he asked if I would like to walk with him down the tracks, I always accepted, holding his hand particularly tight when the big 2-8-0 "shifter" came chuffing by. We could depend on a wave from “the man” in the red wooden caboose, with a hearty, "Hi there, Ted" and a "Hello, Curly" response from Dad. One cold winter day, as I was walking with Dad to work, the crew had parked their engine and caboose at the 14th Street grade crossing near the worker's entrance of Robertson's. They were enjoying a coffee break. The engine crew of the enormous Class H-10 freight-switching locomotive had gone off to the Spaghetti House for some morning doughnuts, leaving their coal firebox roaring orange with flame; air-pumps thumping. Curly was in the caboose alone and spotted Dad through the window. Opening the door to the back platform, he called, "Come on up for a minute, Ted, and bring little Teddy with you!"

He was talking about me! Shakily, I clambered up the steep steel steps ahead of Dad, hanging tightly onto the sooty grab irons. Curly held open the door to his wooden caboose "shanty" and I walked into the cozy interior, warmed by a blazing coal fire in the pot-belly stove where an enamel coffee pot was perking. Curly (who never removed his conductor’s cap) took off his glove and offered his hand. "Welcome to our office, Teddy." This was a real man's world, with its smells of coal smoke, leather cushions, boiled coffee, and sweat! Then Dad said, "I'll have to hurry if I'm going to punch the time clock before the 8 o'clock whistle blows." I turned reluctantly to go. "But Teddy can stay awhile, if he'd like to," Curly said. "I'll show him around a little." He pointed out his desk with its oil lamp and sheaves of train orders and waybills. Then he let me climb up to sit in his seat in the cupola. He showed me his icebox, where he kept his lunch and water bottle. His hand-held lanterns, torpedoes, and fuses were kept in special locked cabinets. "The torpedoes are like big caps; we put them out behind the caboose on the tracks when we're stopped. If another train comes along they'll go off when the wheels hit them; when the engineer hears that sound he knows they're supposed to stop. And the fuses are like flares; they also warn an approaching train that we're stopped ahead." There was a big can of kerosene for lanterns and marker lights in a locked box, and leather-cushioned bunks big enough to stretch out on if a man had to rest up during a long shift. There was a table for eating lunch, and of course the coal bin and shovel, to keep the pot-belly stove hot in the winter. I was in seventh heaven enjoying the grand tour, when Curly's brakeman burst in stamping the snow off his boots. Pointing his glove at me, as if I was an unwelcome invader of their sanctum, the brakeman blurted out, "What the hell is this S.O.B. doing in here?" Curly gripped my shoulder as if to tell me not to worry, and calmly retorted, "There wasn't any S.O.B.s in here until you just came in." End of conversation. I could see what it meant to be the boss of the train. "Well, Teddy, time for us to go to work," Curly said. And he let me climb down the steps all by myself. He waved ahead to the engine crew, who had returned to the cab of the steam engine, and they chuffed away to do their morning rounds as I crunched my way through the snow to school. I always waved at Curly when he came by on his rounds, but that was the only time I got to see the inside of his caboose. A few years later, when I was old enough to hang around the main line with my buddies, I had another caboose experience. In the 1950s, the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad along the Ohio River consisted of four tracks of the heaviest steel rail ever rolled, 155 pounds-per-yard, according to PRR advertisements.

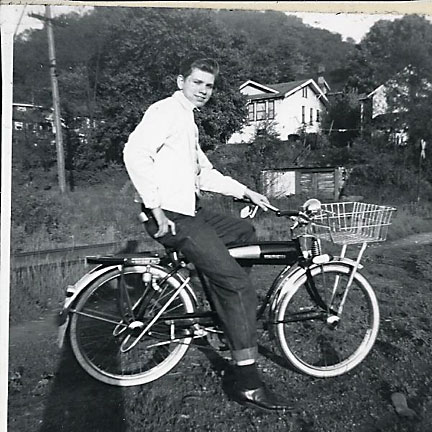

One hot summer vacation day, my best buddy Tony and I had biked up north of town, beyond the water works, and beyond the last street. It was just us, the tracks, the Ohio River, and the mills lining the bluffs on both sides.

We could sit on the grass, just talking of life as teens do, but be entertained by the frequent passing of heavy freight trains, fast passenger trains, and an occasional river towboat with barges. We weren't yet smart enough to bring a water bottle along, but were having too good a time to bother riding back to town to get a drink. A long westbound freight behind a half a million-pound J-1 Texas Type 2-10-4 steam freight locomotive blasted past us.

We began counting cars. 100 cars was not unusual for this type of engine to haul on what was essentially a river level route. When we'd counted 50 cars, the brakes slammed the couplers together. The train slowed down for the approach signals for Conway Railroad Yards. In the fifties, the steel industry was still booming, and there were often jam-ups getting into the yards. By the time we reached cars number 97 or 98, the caboose came along and stopped exactly where we were standing. After all that rumbling of steel wheels on steel rails, all of a sudden it was perfectly quiet. The only sounds were the crickets buzzing in the weeds and the tracks creaking and popping as they expanded under the hot sun. The smells of smoke from about 800 brake shoes, and the creosote being boiled out of the cross ties lay heavily on the still air. We just stood there, wondering where the train crew was, when the back door of the steel main-line caboose opened. The flagman climbed down and slowly walked several hundred yards behind the train with his red flag in hand and a bag of fuses and torpedoes slung over his shoulder. Then the conductor stepped out on the rear platform, checked out the situation, and spotted us standing there in the broiling sun. He waved us over towards his "crummy," which I now knew was railroad slang for caboose.

I hesitated. After all, we weren't supposed to be hanging around the main line, let alone on the rails. And there was a high speed passenger track between us and the caboose. Dad had taught me well about safety precautions around trains. Hidden on the tracks curving around the water works less than a mile away, a speeding passenger train could, without us seeing it coming, be on top of us in 40 seconds flat. Dad told us that once a railroad employee, a "trackwalker" doing an inspection, was caught by surprise and killed by a speeding streamliner. The conductor, sensing our trepidation, shouted over to us, "Don't worry, there are no passengers due for awhile." Well, Dad was supreme authority, but a conductor of a train was authority too. Were we going to be too timid to obey this invitation? With one last look over our shoulders we leaped across the 155 pound rail, onto the steps of the caboose, and followed the conductor inside. The steel caboose looked very much like Curly's wooden "crummy" from years earlier -- except there was no fire in the pot-belly stove. "You kids must be thirsty; want a drink?" We glanced at each other with dry throats as the Pennsy conductor pulled a big jug out of the ice-box, and filled a couple of Dixie cups. I downed the cup in a couple of gulps. I was used to drinking chlorinated city water pumped from wells beneath the Ohio River. "This is the best water I ever tasted," I blurted out. "This is mountain spring water from Altoona. Here, have some more." Why, Altoona was a world away to the east in the high Allegheny Mountains - all of 135 miles away. Altoona - far beyond the range of our second-hand Roadmaster bikes. Altoona! Cool woods with mountain springs pouring forth fresh, icy water just so train crews setting out to cross over Gallitzin Summit and around the Horseshoe Curve could have refreshing drinks. Just then a far-away whistle signal brought us back to the hot Pennsylvania summer. The flagman, having set his torpedoes, came jogging down the ties to rejoin the caboose. The conductor, suddenly businesslike, said, "No passenger trains due on the next track for some time, it's still okay to cross," and escorted us off the back platform and down to the ballast. Dashing across the westbound passenger track back to our bikes, we turned around as the engine crept forward and took up the slack of a hundred freight cars. The caboose was jerked into motion again. A final wave from the platform, and the conductor returned to his office and back to work leaving two junior high school boys suddenly much more aware of a world beyond the Ohio River Valley. These days, the caboose has vanished from American railroading. An American technological wonder called an End-of-Train Device (EOT) is attached to the last car of a freight. Now, instead of receiving a friendly wave from the conductor sitting in his cupola, all you get from the back of most freight trains is a baleful blink from the EOT's red strobe lamp.

The Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, whose tracks are just a half mile from our home in the agricultural country south of Klamath Falls, Oregon, reinstated a caboose for a short time. Every day, at 12:15 pm, a southbound freight passed by down the hill from our property. It consisted of two green diesel locomotives, five to twenty freight cars, and a bright green and gold caboose. When we walked down on Hill Road near the tracks at train time, we could still wave at the caboose, and the conductor sitting up in his cupola would wave back. Just like Curly used to do all those years ago. Would you like to buy a caboose for yourself? Try one of these sites: http://www.cabooses4sale.com/cabooses.html http://www.ozarkmountainrailcar.com/catalog.asp?catid=427 |

|