| |

After years of dashed hopes, I was filled with unbridled eagerness to finally be on my way down. Down more than 80 feet inside the bowels of a 1,300-plus year-old temple/pyramid in the middle of a rain forest. Down a limestone stairway so slippery I had removed my shoes and was sitting on my hiney, reaching out with sodden socks for a foothold before inching forward and downward one step at a time.

| |

|

|

Around each bend of the narrow, corbel vaulted passageway I strained to see my goal: an unassuming triangular stone door. But this chunk of limestone was gateway to one of the most surprising finds in the history of Mesoamerican archaeology: a burial chamber containing perhaps the most extravagant sarcophagus ever found outside ancient Egypt, and undoubtedly one of the most misinterpreted images in existence.

In 1519, Hernan Cortes passed within 30 miles of the Maya city Palenque (pa-LEN-kay) enroute to his annihilation of the Aztec empire. Concealed by the verdant tropical foliage of the Chiapas mountain range, he never saw it. Founded around 200 BCE, the city was an important trading center. It reached its apex between 600 and 750 CE but, like other major powerhouses of the Classic Period such as Tikal and Copán, was into its decline by the beginning of the tenth century. |

|

| |

A hands-down crawl back up the ancient limestone stairway was much easier than the descent. |

|

|

|

| |

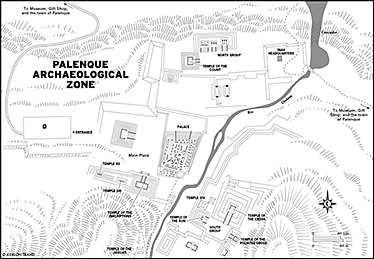

More than 1,500 structures cover an area of some 50 square miles that include extensive residential neighborhoods. Only about three dozen of the buildings have been excavated. Most Maya cities were reliant for their water source either on cenotes - sinkholes in the limestone allowing access to underground rivers of the Yucatán Peninsula - or massive chultuns - underground cisterns used to collect rainwater. Located in one of the highest rainfall regions in Mexico, Palenque was blessed – and cursed – with rivers and rivulets flowing throughout the site. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Most of the excavations have centered around the core groups, heart of Palenque’s social, political and religious activities (image courtesy of Moon.com) |

|

The constant dampness in the region has smeared the stones of this stairway with a centuries-old buildup of condensation. But I no longer care about such trivial details because I finally see my goal: the final resting place of one of the greatest of all Maya rulers, Pakal.

| |

|

|

Ascending the throne in 615 CE at age 12, Kinich Janaab Pakal, a.k.a. Hanab Pakal, Pakal II, Pakal the Great and Lord Shield Pakal, ruled for a remarkable 68 years. Under the reign of Pakal and his son Kan Balam, Palenque enjoyed a combined 86 years of stable and consistent rule during which the city flourished as a major power and center of commerce. Sadly, the accomplishments of and beautiful structures built by this great king are not well known. But his sarcophagus unquestionably is. |

|

| |

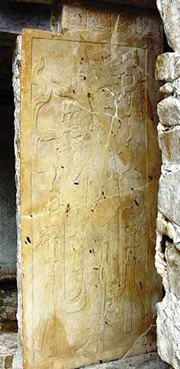

Deep in the Central American rain forest, a simple triangular door sealed with stucco concealed one of the most amazing tombs found outside the deserts of Egypt. |

|

|

|

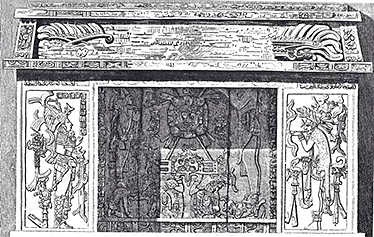

Pakal’s original sarcophagus lid in situ (above left), a life-size replica in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (above middle, image courtesy of LatinAmericanStudies.org), and a painted copper décor piece hanging in my home (above right) which shows the detail of Pakal’s death and resurrection scene.

Often explained as an astronaut, usually of alien origin, ascending into space in an otherworldly conveyance, this scene actually symbolizes Pakal’s death and rebirth. Having just died, he falls down the World Tree, axis mundi of the Maya universe and his pathway from the underworld to the heavens, which are indicated by a skyband at the top of the scene enhanced with symbols of the stars, sun and moon.

Carved from a single block of limestone and weighing nearly 15 tons, the sarcophagus was set in place early during construction of the Temple of Inscriptions and nearly fills the burial chamber. The 12.5-foot by 7-foot sculpted lid tips the scales at 5.5 tons, and is set into a track designed so it could be slid open.

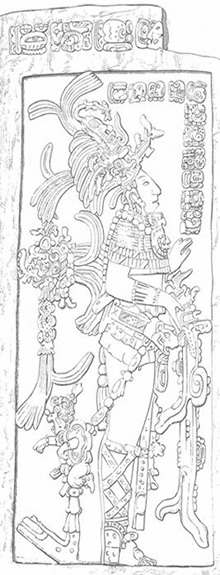

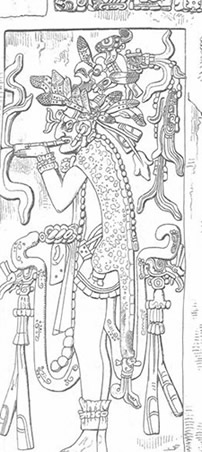

Both the Temple of Inscriptions and adjacent Temple of the Red Queen revealed rich burials. A single carved stucco figure embellishes each of the four piers between the doorways of the Temple of Inscriptions

(above right).

Situated on the south side of the Main Plaza, the Temple of the Inscriptions rises 75 feet making it the tallest edifice in Palenque. The entire structure was sheathed in stucco and painted dark red. A steep and narrow staircase, long closed to the public, climbs the massive pyramidal base to a rectangular temple and provides a magnificent view of the ancient city and surrounding area. Five doorways are separated by piers of sculptured stucco figures, originally painted in blue, yellow and red.

Pier three as it looks today (above left) compared to Frederick Catherwood’s 1840 sketch

and his hand-colored version published in 1844.

Beyond the doorways, a large vaulted chamber is filled with three massive sculpted limestone panels which give the building its name. Second-longest of all Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions, exceeded only by Copán’s Hieroglyphic Stairway, it details Pakal’s lineage for ten previous generations. Pakal was eleventh in a dynastic lineage that extended for 15 rulers.

Although he died in 683, it wasn’t until 1952 that his interment was discovered. Archaeologist Alberto Ruz had spent years puzzling over holes in a slab set in the floor of the inner chamber of the temple, and finally realized the walls extended below the floor. Deducing ropes had been strung in the holes to lower the slab in place, he lifted the stone and discovered a stairway filled with rubble. Thus began a four-year dig to clear 300 tons of debris and uncover the final prize: final resting place of one of the greatest Maya kings.

Pakal was the first burial discovered inside a Mexican pyramid. His body was covered in cinnabar, a toxic ore derived from mercury whose red color was thought to be associated with blood, the rising sun and resurrection. A profusion of jade jewelry adorned his body, his face covered by a stunning mosaic jade mask. It was an astonishing and utterly unexpected discovery. Although the body and priceless objects have been removed and only the sarcophagus lid remains, it was still humbling to finally gaze upon Pakal’s burial crypt.

Inside the Temple of the Red Lady, the body of a woman,

her coffin and all its contents were covered with cinnabar.

Attached to the east side of the Temple of Inscriptions, Temple 13, a.k.a. Temple of the Red Queen, hid a sealed central chamber containing the body of a 40-something-year-old woman. Thought to be Pakal’s mother or grandmother, the chamber was second only to Pakal’s for its rich contents. Although looted in the past, it still held large amounts of jade and pearl items, jewelry and other ornamentals. The walls of the sarcophagus, the 5-1/2-foot-tall body (quite tall for a Maya woman of that time) and all its contents were coated in cinnabar.

The Palace is a massive rambling labyrinth of galleries, chambers and courtyards.

It showcases the Maya’s mastery of the corbelled arch, who used it and other

weight-saving advancements to construct roomier interiors.

Bordering the east side of the Main Plaza, a 33-foot tall platform with a base measuring 240 by 318 feet serves as the base for the Palace. Comprised of approximately 15 separate structures and numerous courtyards, what we see today is the result of centuries of alterations and structures-built-upon-structures leaving subterranean areas. Royal residences were handy to reception galleries and administrative areas; air vents allowed air to move through the rooms; six latrines and two sweat baths serviced the occupants; and running water was enjoyed by all.

| |

One of the most distinctive constructions in all of Meso-America, the Tower rises four stories from a corner area of the Palace. Accessed by a narrow staircase, it may have been used as a lookout or possibly an astronomical observatory. From the Tower, the setting sun at winter solstice lines up with the center of the Temple of Inscriptions.

The curved roof of the Palace was enhanced with roof combs, and walls inside and out, were decorated with modeled stucco scenes from Maya ceremony and mythology. Massive sculpted limestone columns line the galleries, traces of their blue, yellow and red paint still evident. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Two of the Palace columns flank Catherwood’s hand-colored illustration

showing the detail in the pier on the left.

View from the Group of the Cross looks into the Main Plaza

with the Temple of the Inscriptions on the left

and the Palace and its iconic Tower on the right.

Situated on a terraced, leveled hillside overlooking the Main Plaza, the Group of the Cross was built by Kan Balam, Pakal’s son, in the seventh century. The three main temples pay homage to his rise from child heir to ruler of Palenque. The associated cross motifs gave the group its name although the symbol actually represents the World Tree found in Maya mythology.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Tallest in the Cross Group, the Temple of the Cross towers above the Palace and Main Plaza

|

|

Its imposing staircase leads to a central chamber flanked by massive carved panels, shown in Catherwood’s sketch. |

|

Original panels leading to the interior chamber of the Temple of the Cross, with Catherwood’s rendition. Original panels leading to the interior chamber of the Temple of the Cross, with Catherwood’s rendition.

Temple of the Foliated Cross (above left) is the smallest temple in the Cross Group.

From this structure you look down (above right) upon the Temple of the Sun

and the remains of Temple 14.

A life-size limestone panel from Temple 17,

located just south of the Group of the Cross,

depicts Kan Balam and a kneeling captive.

A long gallery on the north edge of the North Group

includes this stucco relief protected from the rain by a thatched roof.

A small Ballcourt (above left) dating to 250 CE sits between the Palace and the North Group.

Bordering the west side of the North Group, the Temple of the Count (above right)

was named for Count Frederick Waldeck, who took up residence here in 1831.

He spent two years drawing and writing about Palenque.

Unfortunately, the results were more fancy than fact.

Investigations of Palenque took many turns and it wasn’t always treated kindly. Rumors of a city lost in the rain forest began circulating in 1773. In 1784, orders from Guatemala dispatched a small group including an architect to visit the site, but their report was lost for a century in the Royal Archives. Two years later the Spanish Crown sent Captain Del Rio to scavenge Palenque for any possible treasure. Hiring nearly 80 local Maya, they set to work on the Palace with axes, billhooks and crowbars, and followed up with a massive bonfire.

Del Rio boasted, “Ultimately there remained neither a window nor a doorway blocked up; a partition that was not thrown down, nor a room, corridor, court, tower, nor subterranean passage in which excavations were not effected (sic)." To complete the devastation, he hacked up and hauled away many pieces of art and architecture, including numerous offerings and artifacts buried beneath temple floors. His report and his plunder were sent to Spain where, once again, it was lost in the Spanish archives.

| |

Fortunately before any more destruction was inflicted, in 1840 two adventurers arrived searching for and documenting ancient Maya sites. John Lloyd Stephens, an American writer, explorer and diplomat, and his friend Frederick Catherwood, an English artist and architect, spent a month at Palenque clearing the jungle and sketching what they found. Their publication of Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan in 1841 stimulated world-wide interest in the Maya civilization. In 1844, Catherwood’s hand-colored lithographs were reproduced in Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán, further lifting the veil on the mysterious world of the Maya. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

An aqueduct adjacent to the Palace illustrates how they were lined with stone, and even flows through an eight-foot-tall vaulted tunnel. |

|

Palenque’s marvelous structures and beautiful stucco and limestone carvings would not have survived the wet climate as well as they have had the ingenious Maya not criss-crossed their city with aqueducts, channels and drains. Not only were the numerous waterways directed into controlled exits from the site, they also delivered running water to the buildings.

The Río Otolum forms a series of picturesque cascades

and swimming holes, such as Banos de la Reina or Queen’s Bath (above right).

Palenque’s waterways channel into the Río Otolum where they eventually become a series of beautiful cascades and form bathing pools such as the Banos de la Reina, or Queen’s Bath. Follow the path downslope from the North Group a little over a half-mile along the river, past more ruins (mostly residential areas), and you’ll reach the highway. Across the road at the Palenque Museum you can delve further into the history and rulers of this marvelous ancient city.

Located in the Mexican state of Chiapas about five miles from the town of the same name, the Palenque archaeological site is accessible by local bus (image courtesy of Weather-Forecast.com).

Note: The Temple of Inscriptions is closed to the public, both for climbing and for accessing Pakal’s incredible tomb. Occasionally, special arrangements can be made to visit the crypt after hours in the accompaniment of a guide and guards from the site. If you have the opportunity, do it!

|

|