| |

“Don’t worry. He'll move,” Felipe assured me. Then, after a brief pause (and was he laughing?) he added, “It won't eat you." I hoped not.

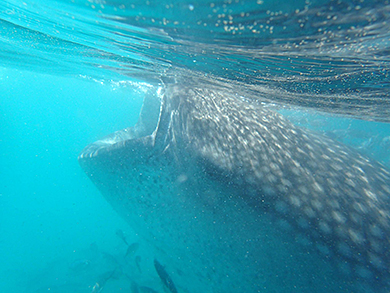

A whale shark getting his fill

We were snorkeling in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez near La Paz. Our group’s search for a whale shark had been successful. Almost, I worried, too successful. A few feet from me was an eye-poppingly massive whale shark, about 24-feet long and weighing about 15,000 pounds. Its most intimidating feature was its 5-foot wide mouth displaying more than 300 rows of teeth. It lazily cruised toward me, gobbling whatever it is whale sharks eat. I hoped that wouldn't include me.

Sure enough, just as Felipe had promised, it shifted its course, searching for tastier morsels. Whale sharks, I learned later, are filter feeders that can process up to 1,500 gallons of water an hour. Along with plankton, they eat krill, fish eggs, sardines, squid and small fish.

Searching for food

Whale sharks - they are sharks, not whales - are the world’s largest fish. The largest verified whale shark was 61.5-feet long and weighed an estimated 47,000 pounds. Although research data is limited, it's believed they reach sexual maturity at about age 30 and live 100 to 150 years. A docile fish, whale sharks are found in relatively warm water, usually 71 degrees or higher.

The behemoth critter near me was big and beautiful, with a wide, flat head with a rounded snout, two small eyes and a cartoonish array of white polka dots, patterns unique to each shark. I snorkeled alongside, and sometimes dove below the shark for other vantages, while cautiously avoiding its flapping tail, which can slap a swimmer unconscious. From underneath and alongside, my view was often obscured by large schools of remora, 1- to 3-foot long suckerfish swimming next to or latched onto the shark. Zipping past, too, were elegantly-swimming manta rays, seemingly flapping their wings like birds flying underwater.

Surrounded by remora

Our original plans envisioned seeking out several whale sharks, but Felipe and the panga captain with our group decided to stay put and enjoy our quietly feeding shark. Friends on a second panga, we learned later, counted 16 whale sharks, but they were smaller and more elusive.

Open wide...

Surprisingly, researchers have collected only limited data for whale sharks, a species believed to have originated 60 million years ago. They are known to travel long distances for food. One was tracked as swimming 8,000 miles. Whale sharks' only predators are humans. They're fished in Taiwan and China for tofu, but they're honored in the Philippines, where they are featured on 100 peso bills, and revered in Vietnam, where they are called Ca Ong, or “Lord Fish.”

Our Lord Fish outing was exhilarating, and provided us with a whale of a tale about a shark with a dangerous tail.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Loading up at the La Paz dock

Jeanne Skalka/Alan Calfree photo |

|

Sergio talks about natural history

|

|

The whale shark outing preceded four nights of kayaking, hiking, swimming and snorkeling on Isla Espiritu Santo, an 11-mile long island north of La Paz. Extremely windy weather prevented us from making the planned paddles, with pangas boating us to beach-front campsites.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Kayaking along sandstone cliffs |

|

Al Glidden and Troy Scott paddling |

|

Our first stop at Coralito came after a rollicking panga ride over tall swells that likely would have swamped our kayaks. We then spent the afternoon kayaking in the bay on a sea as smooth as glass, paddling past remarkable sandstone cliffs wind-carved and eroded into fantastic formations, many like ancient ruins. Blue-footed boobies and brown pelicans circled overhead, but more unusual was a pair of mating sea turtles. The evening sunset was a dizzying display of colors, the sky variously and briefly flavored hues of burgundy, flame red, lipstick pink, shimmering yellow, soft and semi-fluorescent blue and more.

With the forecast predicting more blasting winds, the next morning we scrambled up a nearby ridge, and were rewarded with views of the island's rugged, mostly barren volcanic plains. To the north were a seemingly endless series of ridges and deep-cut valleys. The sparse vegetation was mostly limited to cactus, some standing like multi-armed octopuses, some short and squat, others tall and limbless. At a sandstone outcrop, oyster fossils decorated the rock.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Hiking Isla Espirito Santo, Skalka/Calfree photo |

|

Cactus cover the island, Skalka/Calfree photo |

|

That afternoon several of us snorkled after a short panga ride to Gallo, a nearby island. Because of the winds, we flattened the tents before leaving. When we returned, those who stayed behind told how whipping winds had toppled the tables, sent utensils and anything not tied down flying.

Blue-footed boobies watch from island walls

Our next day's planned panga ride further north was cut short by even taller swells. We retreated instead to Playa Ballena, a beautiful beach where camping is allowed only in emergencies. That night's wind was the wildest yet, seemingly malevolent and intent on ripping our tents or sending them, even with people inside, soaring. Outside wasn't much better - continual bursts of sand that stung like machine-gunned pellets.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Tents along the beach, Skalka/Calfree photo

|

|

Candace Hassinger and Amy DiBartola at a sofa rock on the El Candelero Trail |

|

A final night at El Candelero was the calmest. Along with snorkeling in the bay, some of us hiked the El Candelero Trail, which meanders to a sandstone cave. Mario, one of the guides, told how the cave and surroundings give him a sense of those who came before. That afternoon panga ride deposited some of us at another bay, where the cliff walls meandered in maze-like fashion. Rueben, another guide, waved me over and held out a pufferfish, signaling me to touch and stroke it spongy, soft body before releasing it.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The setting sun cast long shadows

Skalka/Calfree photo |

|

Donna Fontana-Smith returning from snorkeling

|

|

Our final day's panga ride included a detour past a frigate rookery where the males paraded with what looked like large bulbous red balloons, their way of alluring females for mating. At another stop we snorkled along a point marked with unusual rock formations. But even more unusual, when we swam around another point we found ourselves at Bahia Balandra, a large beach with sunbathers, swimmers and rental rubber kayaks and a busy parking lot with food and craft vendors, tour buses and, eventually, vehicles to shuttle us to La Paz.

Sergio and Ruben cooking dinner

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Mike Reeder paddling solo |

|

Trip organizer Margo and Mike McCullough |

|

It hadn't been the trip we'd envisioned but we had eaten well, hiked, snorkled through aquarium-like fish-filled waters and, when the wind wasn't punishing us, enjoyed kaleidoscope-colored sunsets and constellation-filled night skies. In our free time we sat and chatted. Instead of kayaking, we just yakked and yakked.

Bob Marsalli and Kristen Stoimenoff kayaking

| |

Day of the Dead in Lapaz |

|

La Paz Mural |

|

About the author

The author and Sergio enjoying kayak time.

Lee Juillerat is a freelance writer-photographer who writes for various newspapers, including the Klamath Falls Herald and News, where he was the paper's long-time regional editor. He is also a frequent contributor to regional magazines, including Southern Oregon Magazine, Range, Northwest Travel, Range, and Alaska/Horizon in-flight, and the Medford Mail Tribune. He recently published a book, "Lava Beds National Monument," for Arcadia Press. He can be contacted at 337lee337@charter.net. The trip was organized by Margo McCullough of Margo's Travel at http://margostravel.com through ROW Sea Kayak Adventures.

|

|