| |

Every day is a farmer’s market day in many of Peru's cities and villages. Just like Alice's Restaurant, they're places where you can get everything you want. The highlight is a super-duper market selection of local foods—potatoes, cheeses, fruits and vegetables—along with necessaries, everything from mattresses to furniture, clothes, CDs and more.

Cruising the Mercado de San Pedro

During a visit to Peru, a small group spent several days in Cusco, where the incredible farmer's market, Mercado de San Pedro, spills outside its main building onto neighboring streets. We had shorter visits in smaller cities, including Calca, which offer their own bustling markets. But the most dazzling is Cusco's Mercado de San Pedro, a place aromatic in authenticity. Even during the summer tourist season, we were the only non-locals.

The Mercado de San Pedro

Located at an elevation of 11,000 feet above sea level, Cusco was the capital of the historic Inca empire. It may lack that former glory - Lima is Peru's capital - but Cusco's vibrant culture is kept alive at the city’s gathering place, the Plaza de Armas, along with elaborate Catholic cathedrals built atop dismantled Inca temples, and places like the Calle Hatunrumiyou, with its famous 12-angled stone, and Sacsayhuaman (it's pronounced sexy woman") a former Inca fortress in the hills above Cusco.

Meat market, Cusco style

Stacks of fresh breads And fresh fish

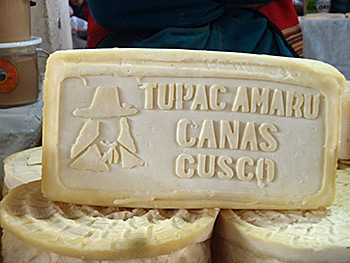

But no place reflects the city’s sense of old and new better than Mercado de San Pedro, a mall-sized farmer’s market that offers a potpourri of foods, local crafts, necessities and oddities. It’s a place where women, some as wrinkled as apple dolls, wear traditional clothing while sitting at stalls selling exotic regional fruits and vegetables, local cheeses, fresh beef and fish, grains, spices, breads, medicinal plants, firewood, every conceivable animal part and, of course, potatoes.

Sacks and sacks of potatoes Everything you want

| |

|

|

Of the world’s 4,500 varieties of potatoes, upwards of 3,800 are grown in Peru. Fittingly, the International Potato Center is based in Lima. Unlike the United States, where potato farmers often own large amounts of land and specialize in specific varieties, the Potato Center estimates 80 percent of Peru’s potato crop is produced by small-scale farmers on less than an acre of land. Amazingly, potatoes grow at oxygen-deprived high elevations, up to 13,000 feet. During a multi-day hike on the Lars Trek, which crosses a 15,000-foot plus mountain pass, we passed high elevation potato fields.

Peruvian potatoes, like those sold in Cusco and other mercados, come in all shapes and colors – pink, white, yellow, purple, violet, red and blue. Some are as small as nuts, others as large as skinny watermelons. |

|

| |

Small potatoes with big taste |

|

|

|

Because of hefty transportation costs, especially from remote mountain regions, many varieties are found only in mercados close to where they’re grown. Some shoppers buy enough to fill small bags while I watched others negotiate for entire sacks. Potatoes are basic to the Peruvian diet because of their low cost and because the many varieties can be used for casseroles, stews, soups and a cook’s creation of gravy and dry dishes. According to the Potato Center, Peruvian adults eat two pounds of potatoes at every meal, 15 times more than Americans.

Fresh local cheese Savoring the grenadilla

The potato choices and uses are spudtacular, but they were just one of the fascinations at the bustling mercados in Cusco and Calca. Along with a cornucopia of locally grown fruits and vegetables, there were stacks of cow skulls and hooves, and hearts and livers. Some are baked or grilled, others are boiled for stews and soups. Locals buying meals from booths at the mercado stands chowed down on soups with floating skulls and hooves but, cowed by the sight, I didn't.

Cusco meats

On my first visit to Cusco’s Mercado de San Pedro, our guide, Manuel, had us sample odd and visually off-putting fruits we likely wouldn't have otherwise tasted. The chirimoyas, or custard apples, were delicious, but more fun was grenadilla, a type of passion fruit. We sampled by tilting our heads back, opening our mouths and sucking in dribbles of freshly squeezed fruit.

The streets of Calca

And Calca, too

Smaller, but even more frenzied was at atmosphere in Calca. As in Cusco, the main market is indoors, but it likewise flows outside onto neighboring streets and passageways. Unlike Cusco, the bargaining and negotiating seemed more intense, with some occasional serious haggling. Although it's a relatively small city, Calca is surrounded by even more rural communities, so shoppers were loading up. It wasn't unusual to see taxis and motorcycles bulging with mountainous supplies of potatoes and beans, and even bundles of firewood.

... And, drool, chocolate

The farmer's markets are fresh food cornucopias, but in Cusco we found an even greater temptation, chocolate. It's just a short stroll from the Mercado de San Pedro and the Plaza de Armas, the city's main square, to the ChocoMuseo, or Chocolate Museum. The free museum's displays are interesting but the true lure is the heady aroma from the googolplex offerings of chocolate bars and hot chocolate samples. When someone suggested we sign up for a chocolate workshop it took minus 30 seconds to sign on.

During the workshop we learned about the origins of chocolate, nimble factoids: 80 percent of chocolate comes from Africa, Peru and Brazil; there are 60 kinds; the Mayans and Aztecs used cocoa as money; pods contain 30 to 60 seeds; the harvest seasons are February and August; the Mayans favored chocolate included chili and honey - and even blood - and reserved the cacao for royalty. We learned about fermenting (five days), covering the batch with banana leaves, and that "roasting is the key to chocolate" and, conversely, "the worst enemy of chocolate is water."

Like water for chocolate, the magical realism was the supernatural transformation of beans to heady varieties of chocolate. After the obligatory tutorial, we roasted and peeled our beans, poured them into bowls and ground them into paste. Then, in a tray with several small bar-sized molds, we added our choice of ingredients: almonds, ginger, cloves, coffee beans, orange peel, milk powder, peanuts, marshmallows, Brazil nuts, mints, coconut and more. The filled trays, affixed with our names, were returned and, after we left, cooked for an hour.

Later that evening a friend and I slipped away from the others, walked to the ChocoMuseo, bagged our group's haul, and returned to our hotel, where we sadly announced that the entire batch had been ruined by a power outage. Then, before the smiles turned into upside down frowns, we confessed. Then ate. It was to drool for.

About the Author

Lee Juillerat writes and photographs for a daily newspaper in Southern Oregon and does freelance work for a variety of magazines and newspapers. He's the author of books about Crater Lake National Park and a frequent contributor to historical journals. Juillerat can be contacted at 337lee337@charter.net.

|

|