Our boatman’s ancestors arrived in much the same manner as our small group: in a wooden boat wending its way down the Usumacinta River. Thick jungle lines both the eastern, Guatemalan bank and the shoreline of Mexico to the west. Palms intermingle with towering mahogany trees, while massive roots of the Maya’s sacred ceiba tree undulate their way across the jungle floor.

We’re in the midst of the Lacandón Jungle, whose heart lies within the UNESCO Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve extending from Chiapas, Mexico, into Guatemala and the southern Yucatán Peninsula. Still dotted with small Maya villages, many of their abandoned cities long buried within this vast rainforest have been revealed, but many more still await discovery. (For more about this region see the December 2013 issue of HighOnAdventure for “Chiapas - or How I Spent Three Days as an Illegal in Mexico” http://www.highonadventure.com/hoa13dec/chiapas/chiapas.htm.)

Approaching Yaxchilán from the Usumacinta River, a few structures bordering the Main Plaza slowly reveal themselves through the nearly impenetrable vegetation.

Fortunately we have a motor which makes it only about an hour’s journey from Frontera Corozal before we catch our first glimpse of Yaxchilán’s limestone buildings gleaming through the thick foliage along the riverbank.

Situated on a 100-foot-tall promontory above an oxbow, the river coils in nearly a full curve about the city almost pinching the peninsula into an island. Yaxchilán (yash-ee-LAWN) served as a local powerhouse and ceremonial center along the ancient Maya’s main trade route between Palenque and Tikal. First populated around the third century CE, Yaxchilán reached its height in the eighth century, and local Lacandón Maya still make regular pilgrimages to burn copal and offer prayers at the site.

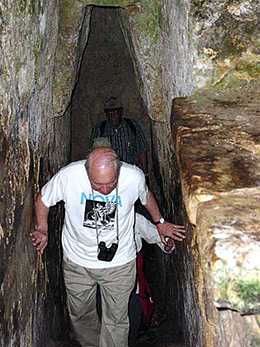

Four darkened doorways lead into corbelled chambers of the labyrinth,

home to a few flying mammals finding refuge from the midday heat and humidity.

Ascending the hillside to first level of the site, not much is revealed except the stone walls of a few low, unremarkable buildings. Muffled under a thick layer of moss and lichen, the city is quiet except for chattering spider monkeys. Even the bats hardly make a rustle as we feel our way along the dark, cool limestone corridors of a creation named the Labyrinth. Emerging from this unusual entry into a Maya city, I am confronted by the large grassy Main Plaza lined with the remains of temples and residences, ballcourts and platforms, and a very tall, very steep pathway leading to more incredible edifices.

| |

Stretching nearly a football field in length along the river, the Main Plaza presents

a tranquil setting with grass-covered grounds, shade trees and wonderfully decorated structures.

|

|

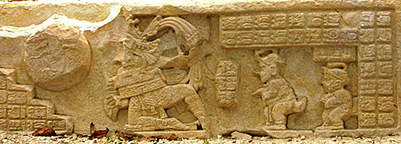

Yaxchilán is famous for the beautiful stone lintels spanning the doorways of 58 structures, each intricately carved with lists of kings and prominent captives, battle scenes and bloodletting rituals. They are complex in their detail and stunning in their beauty. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Artificial plateaus were carved out of the steep topography, and buildings situated to take advantage of cooling breezes off the river. A long stairway climbs nearly 200 feet above the Main Plaza to the South Acropolis and additional terraces, the beautiful pierced roof comb of Structure 33 looming as a promising reward for the effort. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Commanding a view overlooking the Main Plaza, the ornately roofcombed Structure 33 has a Hieroglyphic Stairway with a scene of the famous Maya ball game, Pok-ta-Pok. The above panel depicts a Lord receiving the ball while two dwarfs, held in particular regard by the Maya, look on. A burial discovered in the courtyard has yet to be identified.

The extent of Yaxchilán’s influence is unknown but similar architecture and carved stoned lintels at nearby Bonampak (BOW-nam-pawk) show evidence they may have been under Yax’s control. We know one Bonampak Lord attended the ascension of a Yaxchilán ruler, and another married a Yaxchilán princess.

Only a dozen miles from Yaxchilán as the macaw flies but a longer journey by water and road for land-based creatures, Bonampak set the scholarly Maya world on its head in the mid-20th century. Up to that point, not much was known about this enigmatic pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture. Most of their glyphs had yet to be deciphered and their religion and culture were still a mystery. We knew they were masters of mathematics and astronomy (although the full amount of their knowledge would eventually stun archaeologists), and they built amazing structures and decorated their innumerable cities with beautiful art. What the ceremonial center of Bonampak revealed was astounding.

| |

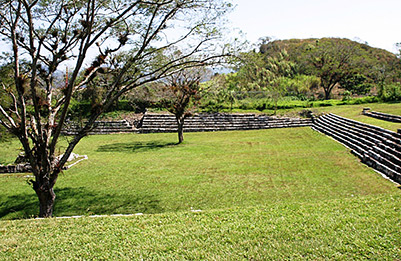

Bonampak’s Great Plaza ends at a hillside terraced with steps and a few simple buildings including Structure 3 (upper left) and Structure 1 (mid-picture right). Stela 1 sits under the thatched roof at plaza level. |

|

The Great Plaza and Stela 1 from Structure 3

|

|

Approaching on foot along a fairly flat roadway about a third-mile from the parking area, Bonampak isn’t particularly impressive. A few low structures define the east and west borders of the Great Plaza. At the southern edge of the excavated portion of the site, a massive stairway ascends a series of terraces atop which are built a few simple structures. Stela 1, Bonampak’s largest, sits at plaza level under a protective cover to lessen erosion from the torrential seasonal rains.

| |

|

|

Elaborately carved stone lintels, such as this scene on Structure 1 of a lord subduing a captive, may have been done by Yaxchilán-trained artisans or by craftsmen brought in from the nearby city. |

|

All three rooms of Structure 1, aka Temple of the Frescoes, are brilliantly adorned with true frescoed murals. Brilliant reds, blues, yellows and greens, applied to the plaster while still wet, were well preserved by centuries of limestone from the ceiling slowly dissolving in the jungle rains, coating the murals with calcite. Unfortunately the first attempts to clean them made use of kerosene, which badly damaged the artwork. Then an opaque salty crust formed as a result of a roof erected to keep them dry. Finally they were carefully cleaned and restored, yet even today just the humid breath of visitors is damaging these 1,200-year-old pieces of art.

Room 1 in the Temple of the Frescoes includes processions of Musicians (above left) and regional Lords (above right) who appear to be celebrating a new heir to the royal lineage.

Each room is decorated, floor to corbelled roof, with varied scenes of life a millennium-and-a-half ago, with almost 300 nearly life-size figures portrayed in remarkable detail. In Room 1, an heir is presented with great fanfare. Richly attired nobles and dignitaries are identified by title, accompanied by celebrating dancers and musicians. In Room 2 war is waged by fierce warriors, their captives presented as tortured and bloodied souls. Room 3 portrays the sacrifice of victims, the victors triumphal rejoicing, and the always popular self-sacrifice/bloodletting rituals for which the Maya are infamous.

The idea the ancient Maya were a gentle, peaceful culture was quickly dispelled with such graphic renderings, their cruel and violent customs now exposed. Much more serene in nature, today’s local Lacandón Maya still come to Bonampak to make offerings of incense, tobacco and candles. No blood.

Near the western edge of the Maya realm, just beyond Montes Azules and a few miles north of the Guatemala border near Montebello Lakes National Park, two smaller Maya cities were flourishing during the same time period. They weren’t making a big splash on the political scene, but living a mostly contented life from first habitation in the third to fourth centuries up until their abandonments in the 13th century.

Chinkultic’s Acropolis sits high on a limestone hillside, its Temple I visible from almost everywhere at the site.

About 150 feet below the Acropolis

is Cenote Agua Azul, the only

water-filled limestone sinkhole

outside the Yucatán Peninsula

Chinkultic’s (cheen-kool-TEEK) cenote is the only one outside the Yucatán Peninsula, although you have to climb the limestone precipice to the Acropolis to see the water source that gave the site it’s name, Maya for “stepped well”. It is the commanding view from this platform high above the Montebello Lakes region, and the magnificent cut stonework by the site’s builders that makes Chinkultic worth a visit.

Many of the nearly 200 buildings at Chinkultic are

clustered in six main groups around large plazas,

among them the Plaza Hundida, aka the Sunken Plaza.

It’s quiet and serene, and you’ll likely have the place to yourself. A series of plazas with low platforms and walls are scattered about the lower grounds. At the far end a small stone bridge crosses the Río Naranjo, and you begin the steep climb up the rocky path towards the Acropolis and Temple I.

Partially restored Temple I, aka El Mirador (left), rises in several tiers and is the tallest structure at Chinkultic.

Also part of the Acropolis are several platforms showcasing some of the beautiful stonework at this site.

About twenty miles west of Chinkultic and a half-dozen miles south of the city of Comitán de Dominguez,

the site of Tenam Puente also makes use of hillside construction and is known for their use of stone,

but in this instance used to buttress the mountain slope and create enormous platforms.

Tenam Puente is built on a mountain top terraced into five levels,

each held at bay by massive retaining walls.

Constructions include platforms, temples, residences, religious and civic buildings, and three ballcourts (above right)

| |

|

Structure 42, above, is comprised of a pyramidal base topped by the remains of three temples, each accessed by

its own stairway. Several human burials were found

during excavation, some in circular tombs, some in graves with walls and roof (right), others cremated and the remains placed in clay pots. |

|

|

|

|

The ancient Maya world includes cities that are bigger, or more impressive, or more politically important, or more beautifully adorned, or that were inhabited centuries longer. But this area of Chiapas, Mexico, so near the border of Guatemala, has played an important part in understanding the ancient Maya. You may even have a serendipitous encounter with some modern day Maya who have come to pay homage to their mysterious ancestors.

|