| |

|

|

| |

Maya Shaman |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Through the smoky haze, enormous flames reach into the night sky while otherworldly figures clad in jaguar pelts and towering feathered headdresses, faces and bodies painted as defense against the powerful forces they were invoking, gyrate around the fire. Seed-pod rattles and anklets create a hypnotic clattering cadence while deep booming drums underlay a sense of foreboding. Overseeing the ceremony is the Halach Uinic, the Maya city’s leader or king, and his Ah Kin or high priest. According to the sky charts, this is a most auspicious time.

There has been endless conjecture, misrepresentation and widely speculative interpretations about December 21, 2012. Countless books have been penned, big-budget movies filmed, incessant television programs aired, peculiar reality series spawned. Ideas are drawn from the legends and prophecies of the ancient Hindu and Hopi, Nostradamus and Edgar Cayce, the I-Ching and Bible … but most of all from the Maya, often including dramatic scenes such as described above.

Did the Maya actually predict December 21, 2012 would be a Doomsday/Apocalypse/End of Days? If we explore their obsession with, perception of, and knowledge about the Universe and Time, we can better understand what they believed to be simply a passage into the next cycle of time. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

We view time in a linear fashion, but to the Maya, time was a cycle which repeated itself, and these recurring sequences could be used to foretell the future. Lacking any sort of telescope, relying only on their keen observations, the astronomical and record keeping calculations made by the ancient Maya are astoundingly accurate. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

El Caracol at Chichén Itzá (left) may be the best known of all Maya observatories. During Mayapan’s heyday from 1200-1450 CE, their observatory (center) was covered in stucco and painted. Ek Balam, in the northern Yucatán as well, also had a circular observatory (right). |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The Maya built observatories in many of their cities, precisely aligning them to monitor the movements of celestial bodies. Most famous of these is El Caracol at Chichén Itzá in the northern Yucatán peninsula, a tall circular building standing on two raised rectangular platforms. Doors at each of the four cardinal points access the 48-foot tall tower with its circular chamber and spiral staircase. In the upper level, windows in the dome are aligned with certain stars on specific dates to facilitate astrological sightings.

To accurately chart the heavens, rather than being oriented to the cardinal directions, El Caracol’s sides are rotated 27.5 degrees, and the corners of the upper base aren’t square. One corner exactly faces the point on the horizon where Venus sets on the eve of its northernmost path, which happens only once every eight years. Another corner points to where the sun rises on the first day of summer, its opposite corner, to where the sun sets on the first day of winter. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

El Caracol’s reflecting pool |

|

Sunken Plaza at Kohunlich |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Reflecting basins assisted astronomers in charting the positions and movements of the planets and stars. These varied from small pools inset in the structure itself, to massive ponds like the large stucco-floored Sunken Plaza at Kohunlich, an hour west of Chetumal, Mexico. The latter included a low stairway-accessed platform projecting into the pool on the east, and another platform, with a short, solid circular construction, bordering the south side. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Structures (left to right) E-1, E-2 and E-3 at Uaxactún comprised the first astronomical observatory complex identified from ancient Mesoamerica, lending its name, “E-Group”, to this type of complex. |

|

| |

A short distance to the west is The Temple of the Masks, the sighting platform for Uaxactún’s E-Group. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Critical to the Maya’s observations of the heavens was development of the E-Group, composed of an observation platform on the west facing a group of three sighting temples to the east. The northern building of the eastern trio marked the position of the spring solstice, the center building aligned with the equinoxes, and the south building lined up with the winter solstice. The first of this type of alignment found in the ancient Maya world was at Uaxactún, Tikal’s nearby neighbor and nemesis. Having been designated Structures E-1, E-2 and E-3, this type of observatory alignment was named an “E-Group.“ E-Groups have been identified at Cahal Pech in Belize, Calakmul in Mexico, and Ceibal, Nakúm and Tikal in Guatemala. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The design of structures comprising an E-Group varied greatly. Structure A-3, part of the E-Group at Ceibal (left), was situated on a limestone plateau overlooking the Río de la Pasión in Guatemala. It was plastered a dark red with an elaborate, brilliantly colored frieze covering the entire cornice. Also in the Petén region, on the banks of the Holmul River, Structure A at Nakúm (right) was part of an E-Group, the remaining structures now mostly rubble. Tallest in a row of five mounds, the building boasts one of the finest roof combs outside of Tikal. |

|

| |

Tikal’s Lost World Pyramid (left) evolved from a small platform into a 100-foot tall pyramid over a 750 year period. Calakmul’s E-Group is comprised of Structure IV (center) and its companion platform, Structure VI (right). |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Sometimes E-Groups evolved over long periods of time. The Lost World Pyramid at Tikal begin around 500 BCE as a small astronomical observation platform facing three small sighting temples to the east. Over the next 750 years the astronomical concept was formalized, including evolution of the small western platform into the 100-foot tall Lost World Pyramid. Importance of the Pyramid’s east-west axis was emphasized by placement of burials and caches. Part way up the west-facing stairway was a platform marking the point at which an observer needed to stand to view the solar phenomena as they related to the other structures in the group. At Calakmul, regional capital and major powerhouse situated just north of the Guatemala border in southern Campeche, Mexico, the middle sighting structure proved to have one of the city’s longest construction periods, spanning 250 BCE to 900 CE. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Famous for its Palace complex, one of the most unique structures in the Maya world, Palenque’s Tower may have been used as an observatory. During the winter solstice, the setting sun lines up directly from the Tower to the center of the Temple of Inscriptions, where the great K'inich Janaab' Pakal was entombed. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Maya astronomical observatories took many forms other than the E-Group. Excavation of Structure I at Becán, situated within the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve of Campeche, Mexico, revealed two 45-foot tall rounded towers on the northern corners. Structural details pointed to these having been used as observatories. Structure VIII at Calakmul, near Becán, was designed on a north-south axis, its three parallel passageways containing doors facing east and west with a line of sight to the east. Another clue this was an astronomical observation post is the building’s deflection approximately eight degrees east of the magnetic pole, and showing evidence of slight modifications over time to correct the alignment of stars.

Deep in the Chiquibul Rain Forest in Belize, the summit of Carol’s observatory, 52-foot tall Structure A3, serves as platform for a building with two rooms. Mixco Viejo’s buildings are grouped in several clusters across flattened ridge tops in Guatemala’s central Highlands, and among the restored constructions are mounds believed to have been used as celestial observatories. Near the northern terminus of Sacbé 8 in Cobá, Mexico, the round-cornered Xaibe pyramid is thought to have been an observatory. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

The Pyramid of Kukulcán, a.k.a. El Castillo, may be the most universally recognizable of all Maya structures. During the equinoxes, its famous descending serpent shadow comes to rest at the giant Kukulcán heads at the base of the stairway. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Important buildings throughout Mundo Maya were aligned such that during the equinoxes and/or solstices the Sun would cast its rays through small structural openings, or create specific light patterns on the exteriors of temples and palaces. Most famous and much celebrated, the Pyramid of Kukulcán at Chichén Itzá is aligned with the equinoxes in a manner that causes the sun to produce a shadow cast by the stepped edge of the pyramid onto the balustrade, resembling a serpent descending the northern staircase. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

During the spring and autumn equinox at Dzibilchaltún in northern Yucatán, the rising sun shines directly through the eastern doorway in the Temple of the Seven Dolls (left). This structure is unique among Maya constructions with its large rectangular windows flanking the doors. Overlooking the Caribbean Sea at Tulúm, the Oratory (right) may have served as a solar calendar. Openings face all four cardinal directions, and at the solstices the sunlight shines directly through the north and south doors.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

The Maya’s calculation of the lunar month came in at 29.5 days, versus 29.53 according to modern science. Their solar year was 365.2422 days; the Atomic Clock says 365.2420 with the possibility of +/-5 at the fourth decimal place. The Maya placed the age of the universe at 16.4 billion years, today estimated at 14.5-15 billion years.

A key to their calculations was understanding what we call the Procession of the Equinoxes, and how the Earth wobbling on its axis slightly changes the celestial alignment every year. Years of meticulous tracking of the procession of the Pleiades, which they thought to be the rattle of the great cosmic serpent, demonstrated that every 72 years, an object rises at the same point on the horizon one day earlier, and thus calculated it would take 26,021 years (25,800 according to modern science) to again rise in the same spot on the original day. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

125 miles west of Guatemala City is one of the largest archaeological sites of the Pacific coastal plains, and one of the most ancient in all Mundo Maya. Takalik Abaj flourished for a thousand years beginning in the eighth century BCE thanks to its location adjacent a major trade route. Slowing being excavated, a large platform known as Structure 7, similar to this one, has been unearthed which contained three rows of monuments carefully placed in a north–south alignment. One row aligned with the constellation Ursa Major, and another with Draco, hints this may have been used for viewing the heavens. |

|

| |

Heart of ancient Tikal, the Great Plaza’s plastered floor covered about 2.5 acres. Some have suggested the seven pyramid-shaped temples constructed around this Plaza were positioned to mimic the Pleiades constellation. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Most amazingly, the ancient Maya knew of the Black Hole in the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, which they called the Great Rift. Using their exceptional astronomical knowledge about the Procession of the Equinoxes, they computed the rare alignment of Sun, Earth and Great Rift would next occur on… December 21, 2012.

The Maya determined the complex synodic cycle of Venus, the point at which a celestial object makes one full orbit, to be 584 days. Modern science says it takes 593.92 days. They set orbit the of Mars at 780 days versus today’s 779.94. Easily predicting solar and lunar eclipses, evidence suggests they also plotted the cycles of Jupiter. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

An elaborately carved stucco frieze adorns the upper portion of Structure A-6 at Xunantunich, Belize. Preserved by its burial beneath a later construction, it incorporates astronomical signs, and glyphs and symbols aligning the sovereignty of their rulers with the heavens. |

|

| |

In Mexico’s Puuc Region, Uxmal’s Temple of Venus, part of the Nunnery Quadrangle, has hundreds of Venus symbols in the frieze of its upper façade. Venus was important as a celestial body, an element of Maya mythology, and was the Maya patron god of war. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Celestial symbols were important in Maya art and architecture. Murals and carvings depict their rulers wearing symbols of the heavens including a belt or “sky-band” made of a chain of symbols relating to the Moon, Sun, Venus, day, night and the sky. They hold staffs decorated as sky-bands as a sign of their heavenly power. Kings associated themselves with favorable gods, and along with their priests would attire themselves in jaguar pelts, the animal’s spots representing the stars.

The ability to record time is frequently acknowledged as a characteristic of “civilization”. Of all the ancient world's timekeeping systems, the Maya combination of solar, lunar, astronomical and ceremonial timekeeping was the most complex and accurate. The Haab or “Vague Year” was their secular calendar, based on a solar cycle of the Earth's 365-day rotation around the sun. It was divided into 18 months of 20 days plus a period of 5 days

The Tzolk'in or “Sacred Round” was a shorter sequence of 260 days (13 periods of 20 days), based on the cycles of the Pleiades and used for sacred rituals and astrological predictions. Also referred to as the “day count”, each day of the Tzolk’in corresponds to a different deity, animal or force of nature and their connected portents and prophecies. It determined the pattern of ceremonial life and the auspicious dates for alliances or launching a “star war” (for more information about “Star Wars”, see “Lords of the Petén, Guatemala” http://highonadventure.com/Hoa06apr/Vicki/Peten.htm ). In use without interruption for at least 2300 years, the Sacred Round count is still maintained for divination and other shamanistic endeavors. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

This Ball Court at Izapa is aligned with the sunrise on the winter solstice. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The Maya calendar in its final form probably dates from around the 1st century BCE, and is thought to have originated with the Olmecs, with Izapa playing a crucial part in its development. Inhabited for nearly 3,000 years beginning around 1,800 BCE, Izapa’s influence extended up and down the Pacific Coast. It was a powerful city-state and trading center, dominating the region for a millennium. Located in Chiapas, Mexico, near the Guatemala border, the number of days in the Tzolk’in calendar at this latitude equals the exact number of days between solar zenith passages, the two days of the year when the sun is exactly overhead. One of those days at this latitude is August 11, the date corresponding to the beginning of the Long Count in 3114 BCE. The alignment of some structures at Izapa and the carving on Stela 25 are believed to be a representation of the galactic alignment as it will appear at the end of the Long Count, which will occur on December 21, 2012.

The Haab and Tzolk’in calendars were interrelated and, taken together, gave a more precise count than our modern Gregorian calendar. Every day had two names, one according to the Haab and one for the Tzolk’in. The two calendars intertwined so the same combination of day names only coincided every 52 years, and this was known as the Calendar Round. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

Stele C at Quiriguá, Guatemala, bears the longest hieroglyphic description of the Maya Creation Myth yet found, noting that it took place on 13.0.0.0.0, the only known monument that identifies this date. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Most significant is the Maya “Long Count” or Tziikhaab calendar. The number 13 being especially sacred to the Maya, they believed that every 13 Bak’tuns, or 5125 years, a new creation cycle begins. They calculated the beginning of the current, or fifth, creation cycle to have occurred on 4 Ajaw 8 Kumk'u or August 11, 3114 BCE, documented in their calendar system as 13.0.0.0.0. On December 21, 2012, the current or 13th Ba’ktun will end, and on December 22 the Long Count will reach 13.0.0.0.0 again for the first time in 5125 years. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

High above the west bank of the Usumacinta River, a beautiful pierced roof comb embellishes Structure 33 at Yaxchilán. Its Hieroglyphic Stairway portrays a ball game and includes a Long Count date prior to the current bak’tun. |

|

| |

Tablets in Palenque’s Group of the Cross temples refer to a date of December 9, 3121 BCE, seven years prior to the beginning of the current bak’tun. Other texts in these temples made note of the rare conjunction of the moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn in July 690 CE. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

The sides and back of Stele 10 on the Great Plaza in Tikal include hieroglyphs that refer to 19 piktunes – a date millions of years in the future. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Dictionary of Maya Timekeeping Terms K’in = day (which was also their word for “sun”) Uinal = a “month” of 20 k’ins/days Tun = a “year” of 18 uinals (360 k’ins/days) K’atun = 20 tuns (360 unials or 7,200 k’ins/days) Bak’tun = 20 k’atuns (400 tuns/years* or 7,200 unials or 144,00 k’ins/days)

*the precision of Maya timekeeping resulted in a bak’tun equivalent to 394 rather than 400 Gregorian years

Other calendars include multiple 18-month lunar cycles, regional variants of the Haab and Tzolk’in, a 9-day Lords of the Night cycle, and yet-to-be-understood 7-day and 819-day cycles. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

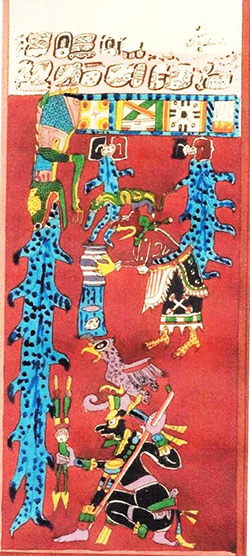

Nothing from the ancient Maya or elsewhere in Mesoamerica foretells of a disaster in 2012, although doomsday theorists point to the last page of the Dresden Codex as evidence of an impending deluge. Created in the 13-14th Century, this accordion-folded bark paper book documents amazing astronomical calculations and charts and associated rituals. On the last page water seems to be gushing from the mouth and from sun/moon glyphs on the underbelly of a sky caiman, who forms a sky-band near the top of the page. A claw-footed creature with a serpent headdress (believed to be Ixchel, goddess of the moon and fertility, in her old woman “destructive” appearance) empties more water from a vessel. Below her a black figure (thought to be God L in his warrior guise) wields spear and atlatl. We don’t know if this is a prophecy for the future, a chronicle from history (the Maya believed the last/fourth world ended by water), or just an intriguing illustration from a misunderstood story.

image courtesy of FAMSI.org |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Monument 6 from Tortuguero, in Tabasco, Mexico, is the only known Maya prediction that actually refers to 2012. Damaged and with two glyphs nearly obliterated, it seems to describe a bak’tun ending event when some god or gods (“Bolon Yokte”) will descend to their home or temple. Bolon Yokte was a god associated with war and creation and change, and possibly used to refer to a group of deities who together comprise the Lords of the Underworld. |

|

| |

|

|

Last year in Comalcalco, about 65 miles north of Tortuguero, a 1300-year-old sun-dried mud brick fragment was found. Facing inward, hidden from view, it contained a Long Count date equivalent to December 21, although unlike Monument 6 it does not have a “future tense” indicator so we don’t know if it refers to 2012 or some historic date. December 21 has always been important to the Maya as the date of the Winter Solstice. |

|

| |

|

|

A tablet in the Temple of Inscriptions at Palenque, in Chiapas, Mexico, refers to a date in 4,772 CE, when they would be celebrating the anniversary of the coronation of their great King Pakal, so it seems they planned on someone being around beyond 2012. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Some believe December 21, 2012 will be a new awakening, others that a cosmic event will unfold. No one can predict what Mother Nature or the Universe waits to unveil. An unknown projectile from space may strike earth. Massive earthquakes or eruptions might tear at the planet’s crust. There may be more tsunami or seemingly endless rains. We are warned of global warming and possible polar shifts and all sorts of gloom and doom.

One of these might happen to coincide with December 21, 2012, but don’t lay it at the jaguar skin-booted feet of the Maya. Their precise study of the galaxy and its celestial bodies, and the elaborate calendars they created, only lead them to believe the next Bak’tun would be the beginning of a new cycle, and we WILL be around to make the best of it.

“Maya” versus “Mayan”

Some years ago, Maya scholars decided that the adjective "Mayan" should be used exclusively to refer to the Mayan languages, and the adjective or noun “Maya” used for everything else. Examples of the proper use of these include: "Maya calendar," "Maya art," "Maya culture," "the ancient Maya," "Yucatec Mayan," "Mayan words," "Mayan speech," and “spoken in Mayan".

Moon Maya 2012: A Guide to Celebrations in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize & Honduras by Joshua Berman

Although the listing of tours and events directly related to 2012 are drawing to a wane, this 127-page guide includes a nice overview and maps of the more well-known ancient sites in Mundo Maya. It also offers tips on travel in Central America from someone who actually lived, worked, and led trips and experienced adventures throughout the region. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|