|

To the Spanish, who were among the region's earliest settlers, Manzanar

is the word for "apple orchard." To generations of another group

of people with a shorter history, Manzanar is associated with World War

II, when more than 10,000 Japanese Americans were held at Manzanar's hastily

developed "relocation center" during the hysteria of anti-Japanese

sentiment following the December 7, 1941, Japanese invasion of bombing

of Pearl Harbor.

|

Visiting Manzanar National Historic Monument

is taking a glimpse at an unfortunate chapter in American history.

Located in Southern California's Owens Valley in the shadow of the

Sierra Nevada Range, Manzanar was one of 10 relocation camps established

by the United States government Within months, and without due process,

120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of them American citizens by

birth, had been sent to camps because of concerns that sympathetic

Japanese might assist their homeland and, to a lesser degree, fears

that angry Anglo-Americans might seek vengeance again "Japs." |

| |

|

Manzanar gained national attention from the book, "Farewell to Manzanar."

It remains the only of the 10 with an active interpretive program that

tells the story of life in an internment camp. Another camp, Minidoka

in Idaho, is also under the wing of the National Park Service, but it

is not yet developed. Just south of the Oregon-California border, Tule

Lake, which became the most infamous because it became the largest and

was designated a segregation center for "disloyal" internees

in July 1943, hopes to develop a small interpretive area around one of

its remaining buildings, a stockade called by Japanese Americans as a

prison within a prison.

Manzanar and the other camps were created following Executive Order 9066

in February 1941. The order authorized the relocation and-or internment

of anyone who might threaten the U.S. war effort. Centers were eventually

located at Manzanar and Tule Lake in California, Minidoka in Idaho, Topaz

in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Granada in Colorado, Heart

Mountain in Wyoming, and Rohwer and Jerome in Arkansas. The first Japanese

Americans who arrived at Manzanar in March 1942 were volunteers who helped

build the camp. By September, more than 10,000 Japanese Americans were

packed into 504 barracks within a 500-acre housing section, which was

enclosed by barbed wire fences and eight guard towers. Insights to life

at camp are told in "Farewell to Manzanar," a book by Jeanne

Wakatsuki Houston and James Houston about her childhood years at the camp.

| A sense of that life is created through a variety of

carefully planed exhibits in Manzanar's former auditorium, which has

been redeveloped into a National Park Service interpretive center.

Originally built by internees in 1944, it housed a gymnasium and a

stage used for plays, graduation ceremonies and other social functions.

When Manzanar was opened April 24, 2004, the auditorium had been converted

into a visitor center. Along with serving as a starting point for

a self-guided auto tour of the old camp, it features a variety of

exhibits intended to give visitors a sense of camp life. |

|

| |

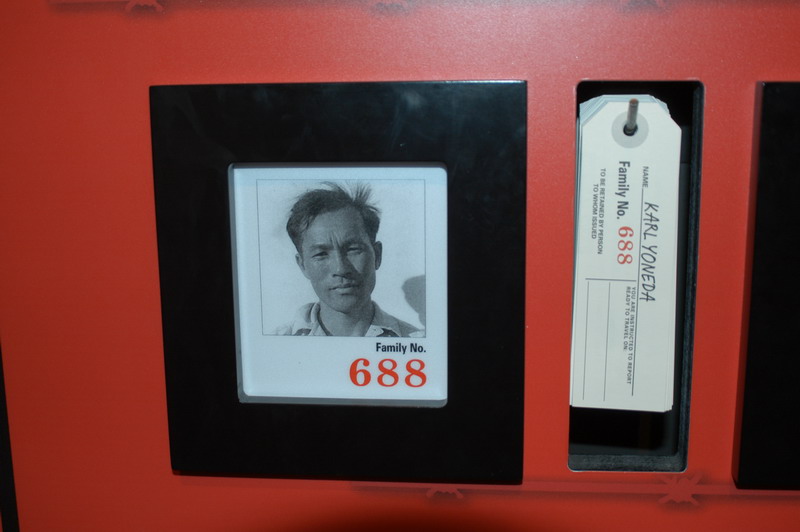

ID Badge for our "Guests."

|

For those forced to live at Manzanar, it was often a difficult experience.

On December 6, 1942, military police shot at Manzanar internees who were

protesting the arrest of another internee. Eleven people were shot, and

two died from injuries. One of Manzanar's most poignant reminders of the

past is the center's cemetery. A monument was commissioned by internees

to honor the 135 people who died at Manzanar. Stonemason Rozo Kado, who

also designed and supervised the construction of the camp's sentry and

police posts, supervised its construction. Each family donated 15 cents

to buy cement. Three characters on the front side of the monument translate

to "soul consoling tower" or, based on the translation, "monument

to console the souls of the dead.

|

|

|

|

Manzanar's cemetery

|

Graves in the Sand

|

Flowers for the Dead

|

Of the original barracks, only one remains. Plans call for rehabilitating

the barracks to better give visitors a sense of camp life. The camp had

504 barracks organized into 36 blocks. Between 20 and 400 people lived

in each block, with 14 barracks, each divided into four rooms. Each block

had shared men's and women's toilets and showers, laundry and mess hall.

One outdoor faucet provided water for each barracks. Up to eight people

lived in 20- by 25-foot rooms. Most of the Japanese Americans sent to

Manzanar were from Los Angeles, 200 miles away, or communities in California

and Washington. Most were unprepared, and unaccustomed, to the harsh summer

heat and below freezing temperatures of winter. Because of its desert

environment, the camp was frequent made miserable when strong winds carried

dust and sand.

|

|

|

|

Last of hundreds of barracks

|

Banners of the 10 Camps

|

Interpretive Center

|

A 3.5 mile auto tour bisects the camp. While simple glimpses out a car

window provide a sense of the camp, it's also worthwhile to around sections

of the camp, especially through rock gardens created by internees to create

a sense of atmosphere and beauty, and the cemetery. It's possible to ponder

the past while walking through the grounds and seeing scattered remnants,

including concrete pier blocks where barracks and other buildings once

stood. Most of the driving routes stops show where various camp locations

, including a high school, newspaper, baseball fields, Catholic church,

children's village, Buddhist temple and other structures, were located.

At most, all that remains are foundations or concrete slabs. Future plans

include eventually reconstructing or restoring two barracks, a mess hall

guard tower and the rock gardens.

As WWII turned in favor of U.S. troops, the number of internees gradually

decreased. After hitting a peak population of 10,046 in September 1942,

the camp's population shrunk to 6,000 in 1944. The last few hundred internees

left in November1945, three month's after the war ended with Japan's surrender

on August 14, 1945.

Over the past 30 years, annual Manzanar Pilgrimages have been held the

last Saturday of April, with the cemetery serving as the prime gathering

place. Featured activities include an interfaith memorial, guided tours,

displays, presentations and music. For information, contact the Manzanar

Committee, 1566 Curran Street, Los Angeles, CA 90026 or telephone (323)

662-5102. For information on Manzanar, visit the Web site at www.nps.gov/manz

or write Manzanar National Historic Site, P.O. Box 426, Independence,

CA 93526. Manzanar is about 200 miles from Los Angeles off Highway 395.

The camp is nine miles north of Lone Pine and six miles south of Independence,

where the Eastern California Museum exhibits include "The Story of

Manzanar, the Japanese American World War II Internment Center.

|